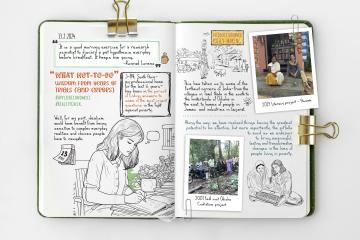

Part 2 | What Not-to-do: Wisdom from Years of Trials (and Errors)

Why are short term gains more tempting over long term thinking? Why do we inadvertently go for the low(est) hanging fruit, the path of least resistance? With these questions comes my What Not-to-do List – three key lessons learned from sixteen years of co-creating and testing solutions at the margins, for a world made kinder for the poor through policies and programmes informed by rigorous evidence.

In Lesson #1: Do not look for the silver bullet, I discussed mythbusters that required us, our researchers, and our partners to put on our thinking caps, and shared lessons on what we have learned from unexpected outcomes and unanticipated impact.

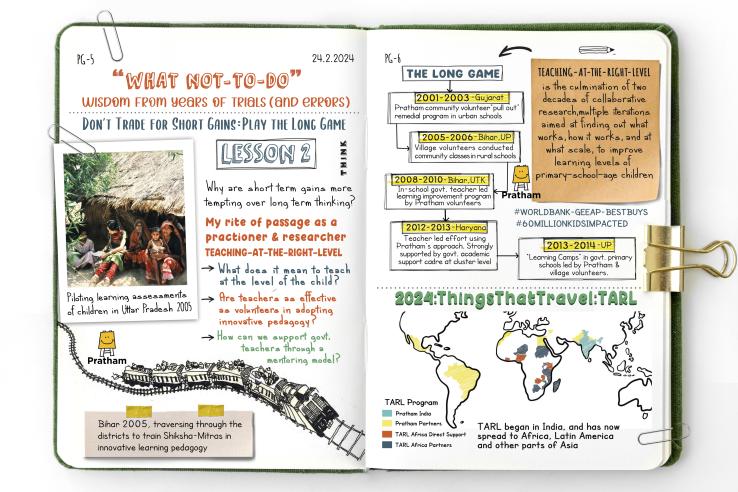

Lesson #2: Don’t trade for short gains – Play the long game

This lesson emerges from our partnerships and research in our 20-year journey globally, and sixteen years in South Asia, which have impacted over 600 million lives through our collaborative work.

My first exposure to understanding development issues on the ground, using measurement techniques to unpack the problem and co-create locally grounded solutions—my rite of passage as a practitioner and researcher—takes me back to 2005. It was around that year when the Bihar government announced hiring over 80,000 para-teachers (shiksha-mitras) to be placed in government schools. As a young field research associate, I found myself in the hinterlands of Bihar over the next month, assisting the Pratham teams as they painstakingly traveled across 150 locations in Bihar’s far flung districts, training a core team of government Master Trainers who would then go on to train these para-teachers. It was no small task. In the true Pratham style of learning by doing, training was not imparted through classroom sessions; rather, hundreds of master trainers were taken to the field and engaged in daily practice classes with children. Pratham could have chosen the traditional in-classroom training which would have been less of a logistical challenge, and the trainees would also have been happy to catch that much needed mid-afternoon nap. But taking the harder path taught us all an invaluable lesson: how to get master-trainers to do the practice classes in a do-it-yourself style, at a large scale, with quality and rigour, who can then percolate their experience to the teachers.

In the subsequent years, this learning was refined in Uttar Pradesh, through training over 700 volunteers, who were mobilised to conduct remedial classes for children who were lagging behind. As part of Pratham’s “rural catalytic team,” we spent months in the villages of Gauriganj, in deep conversations with parents and school teachers, unpacking what learning meant to them. As child after child stumbled in their oral reading (ASER) assessments, aam sabhas (village meetings) were held and parents began blaming their children first and then the teachers. Village report cards co-created through local community participation pointed to the glaring learning problem. A generation of youth stepped forward to help conduct remedial classes for these children.

Here began the early avatars of Teaching-at-the-Right-Level (TaRL). Over the next fifteen years, Pratham and J-PAL leadership, alongside our affiliated researchers, conducted half a dozen randomised evaluations to answer several related questions: What does it mean to teach to the level of the child? Are teachers as effective as volunteers in conducting remedial classes? Can this pedagogy be done through learning camps in shorter bursts? How can we support government teachers in classrooms through a mentoring model? and more.

Till date, this series of research and scale efforts focused on reorienting instruction has improved learning opportunities for over 60 million students in India and Africa, in close partnership with governments. It all started with a simple theory and taking a long view to the solutioning—that school teachers were not to blame for learning lags; it was the tyranny of the curriculum that was the main problem. Pedagogy and teaching effort tailored to the child’s need can have significant impact, even within government systems when taught by teachers, provided this is the primary focus of their work. And this problem cannot be solved overnight; rather, it needs reorienting pedagogy, teaching effort and the supporting systems, and a good amount of learning and unlearning to enable the shift.

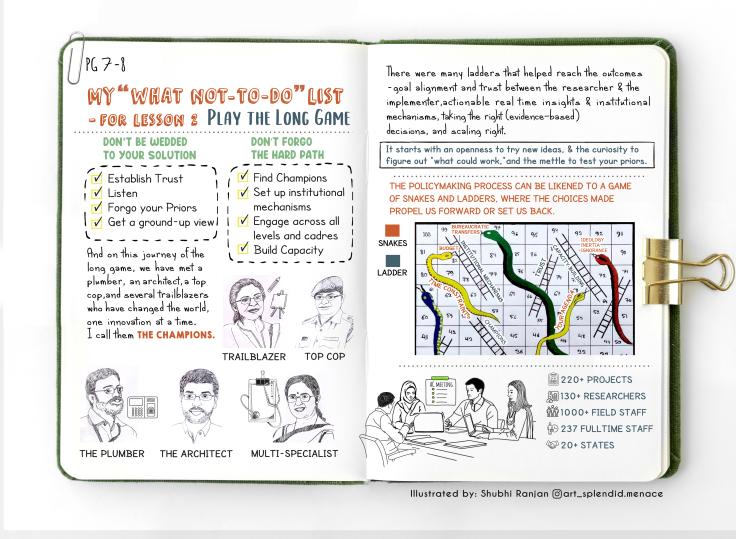

Taking the long view to a holistic engagement. This pretty much sums up the What-not-do for enabling a successful partnership as you take the long view.

- Don’t be in a hurry to get across your own agenda. Establish trust. Listen to your counterpart. Read between the lines. Get the bottom-up view.

- Don’t be wedded to your solution. Ditch a good idea if you have no buy-in. Forgo your priors and meet halfway to create locally-grounded solutions that you can then test collaboratively.

- Don’t be tempted to forgo the harder path of building and strengthening the implementer's (government or NGO’s) own capacity and systems. It is easy to embed and replace with your teched up staff. But in hindsight, this does not contribute to a long-term systems-change approach.

- Don’t forgo the time it takes to create the right institutional mechanisms in favour of expediency if your ultimate goal is to create an enabling ecosystem to adopt evidence-based approaches.

Each collaboration between an implementing partner, the government, and an organization like J-PAL contributes to a deeper understanding of how policymakers and researchers can work together to devise, assess, and scale innovative solutions aimed at reducing poverty.

There were many ladders that helped reach the outcomes for the example I have illustrated here—goal alignment and trust between the researcher and the implementer, actionable real-time insights and institutional mechanisms, taking the right (evidence-based) decisions, and scaling right. Most importantly, it starts with an openness to try new ideas, and the curiosity to figure out “what could work," and the mettle to test your priors.

Teaching at the Right-Level (TaRL) had the right set of ladders, and willing co-conspirators in the Pratham leadership, government partners, and J-PAL’s affiliated researchers. It is the culmination of two decades of collaborative research, multiple iterations aimed at finding out what works, how it works, and at what scale, to improve learning levels of primary-school-age children. The TaRL approach has found a top spot in World Bank’s GEEAP list of best-buys.

Champions. And on this journey of the long game, we have met a plumber, an architect, a top cop, and several trailblazers who have changed the world, one innovation at a time. I call them the Champions. They taught us not to settle for the short run. Through them, I have learnt to bridge the political with the bureaucratic, experienced how things travel through generalisability, and acquired the know-how to shape our insights. We have seen what one can do when we take the long view and have the right collaborators, in the right place, at the right time. From testing theories to debunking beliefs, joining forces with collaborators from governments, non-profit and academia has led to scaling several successful programmes in India to reach millions of people:

- an innovative nationwide fund flow reform first introduced in Bihar that reduced corruption and improved program efficiency through more efficient fund distribution;

- a pathbreaking emissions trading scheme for particulate matter to reduce air pollution through a decade-long partnership with Gujarat’s Pollution Control Board to expand to hundreds of industry clusters;

- scaling programs aimed at changing gender attitudes and deeply ingrained norms for an entire generation of adolescents through long term partnerships in Punjab and Odisha;

- multi-faceted livelihood programs that work for India’s ultra-poor, scaled to reach over one million in Bihar through a deep and long term partnership with the Rural Development Department— the list goes on.

Institutional Mechanisms. Capacity Building. Over the past decade, we've understood the challenges in aligning the requirements and constraints of implementers, policymakers, and researchers, while recognising the significant benefits of such partnerships. Furthermore, a longer-term systems-driven approach which includes institutional mechanisms and capacity building alongside co-creation (identifying the problems and testing solutions), can lead to increased sensitivity and reception to data-driven decision-making among governments. Among J-PAL’s most extensive institutional partners has been the Tamil Nadu government, which includes a deeply embedded life-cycle approach forging linkages between research, capacity building, and policy advisory. Launched in 2013, the partnership began with a months-long policy-research dialogue that brought together a dozen professors and researchers from J-PAL and secretaries of various departments. They discussed key priorities of the state and the latest scientific evidence from around the world on these issues. This led to the design of innovative pilots that address the challenges, and evaluations to measure their impact.

Beyond each individual project or collaboration, there has been a larger commitment that gets recorded through a Memorandum of Understanding and a Steering/Advisory Committee that meets and debates and approves each project. Interim results and operational insights have proven invaluable in responding to local priorities, and enabled us to be responsive and build relationships to facilitate a more effective collaboration between researchers and policymakers. Our teams have also engaged in a series of efforts to strengthen government capacity and leveraging administrative data for use in decision making. Over the past few years, we have provided technical advisory and trainings ranging from sampling, questionnaire design, and data quality, through on-ground shadowing and experiential learning. Several of these practices have since been adopted by the department to ensure the quality of data for future rounds. This partnership with Tamil Nadu has demonstrated a model to partner with other states through institutional partnerships in Odisha, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh, among others.

The policymaking process can be likened to a game of snakes and ladders, where our choices propel us forward or set us back. That is another story for another day. But through this we recognise that to reach 100, we are in for the long haul. That's my Lesson #2.

It is tempting for us to look for quick fixes for policy problems. Their appeal is obvious. Some of these solutions may even look like a surefire success, and they might even be so in the short term. But more often than not, such "band-aid solutions" may fall apart. We need to stop looking for superficial solutions to tackle a problem as vexing and as multi-dimensional as poverty. In other words, stick it out and play the long game.

And while we are at it, don’t underestimate your beliefs (pun intended). That is my Lesson #3: Stay tuned.

Related Content

What not-to-do: Wisdom from years of trials (and errors)

Institutionalizing a culture of evidence-informed policymaking in Tamil Nadu