Long-Term Effects of a Conditional Cash Transfer Program in Nicaragua

- Children

- Parents

- Women and girls

- Youth

- Dropout and graduation

- Enrollment and attendance

- Student learning

- Age of marriage

- Fertility/pregnancy

- Long-term results

- Cash transfers

- Conditional cash transfers

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) are a common intervention to address poverty, but the long-term impacts of their timing on health, education, and labor market outcomes are not well-understood. Researchers worked with the Government of Nicaragua to evaluate the long-term impact of time-limited CCTs on education, reproductive health, and labor market outcomes. Ten years later, people whose families were offered cash transfers when they were younger children had higher labor force participation and earnings on average than people whose families were offered cash transfers when they were older children.

Policy issue

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) may increase earnings in adulthood by allowing higher investment in human capital during childhood. Specifically, conditional cash transfers (CCTs) are a popular intervention aimed at increasing human capital investments. CCTs span more than 60 countries and cover 25 percent of the population of Latin America. Though numerous studies indicate that CCTs improve children’s health, nutrition, and schooling in the short term, there is limited evidence on the long-term impacts of CCTs on human capital and labor market outcomes. This evaluation seeks to understand the impacts of a CCT on education, health, and labor market outcomes in the long-term.

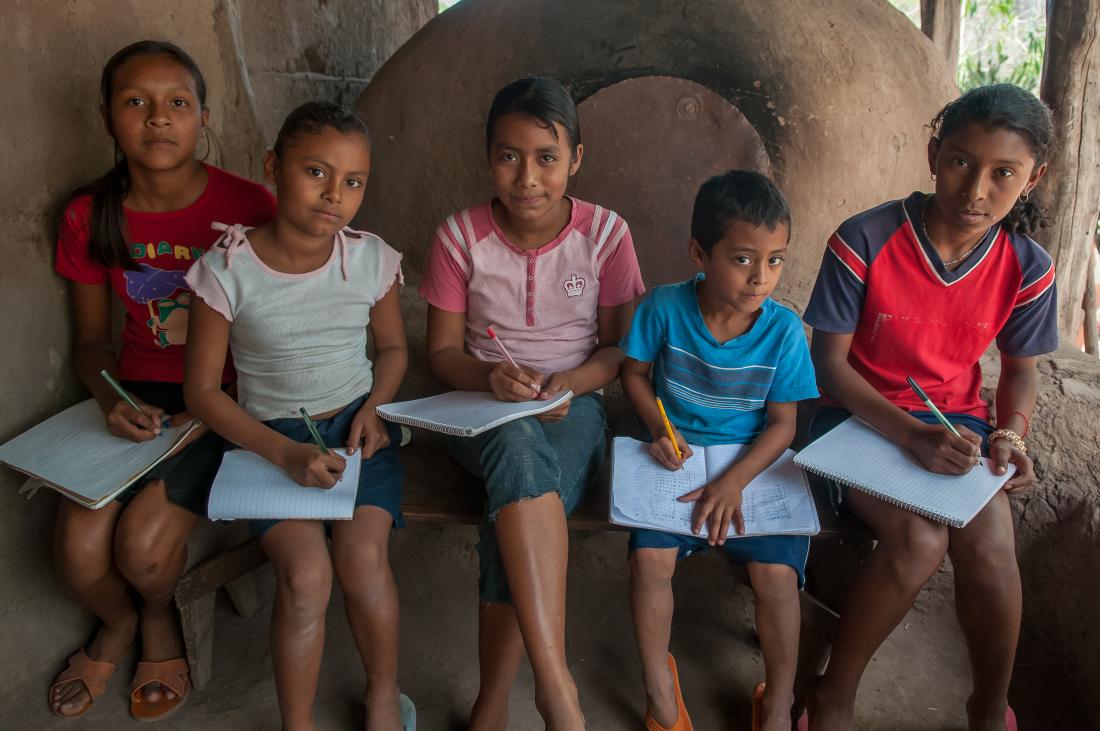

Context of the evaluation

This evaluation was part of the rollout of a new CCT program by the Nicaraguan government, Red de Protección Social (RPS). The evaluation focused on low-income households in three rural regions of central and northern Nicaragua. Areas included in the program had a high proportion of low-income households and low average educational attainment and health indicators. The program sought to reduce short- and long-term household poverty and increase the proportion of children who received preventive healthcare and remained in primary school.

All households in the study were eligible for a cash transfer every other month, conditional on preventive health visits for all under-five children living in the household and on a household member attending health education sessions. Households with children between seven and thirteen years old who had not yet completed the first four grades of primary school were eligible for a second set of transfers every other month contingent on school attendance. Households eligible for this transfer also received an annual transfer meant for school supplies. Households were eligible for the program for a maximum of three years. On average, total transfers were equivalent to roughly one-fifth of average household expenditures prior to the program.

The government also increased the availability of preventive care in parallel with the program.

Details of the intervention

Researchers partnered with the Nicaraguan government’s CCT program Red de Protección Social (RPS) to conduct a randomized evaluation on the impact of the cash transfers on health, education, and labor market outcomes. In particular, researchers and the government hoped to measure the differential impact of the timing of CCTs on children who were between nine and twelve years old in 2000. They hoped to quantify the impact of receiving cash transfers earlier versus later in childhood.

Forty-two rural localities were randomly assigned into one of two groups:

- Early treatment group: The early treatment group was eligible for transfers for three years, between 2000 and 2003. Children in the early treatment group were thus between nine and fifteen years old during the treatment period.

- Late treatment group: The late treatment group was eligible for the same transfers between 2003 and 2005. Children in the late treatment group were thus between twelve and eighteen during the treatment period. Adolescents in this group were required to enroll and reproductive health workshops, and had access to contraception through their healthcare providers.

Each treatment group received transfers for three years, and was not eligible for transfers during the remainder of the study period.

Researchers used data from a program census, two national censuses, and four waves of surveys. The initial program census provided information on baseline characteristics, including demographics and assets. The national censuses provided supplemental information on demographics and education. The four survey waves collected data on labor market history, reproductive and socio-emotional health, education and cognitive skills, and nutrition and household food consumption.

Results and policy lessons

Ten years after the start of the intervention, participants who were offered the program as younger children had, on average, higher labor force participation and earnings than participants offered the program when they were older. There were no significant differences in psychological wellbeing. Among women, fertility was a key driver of improved labor market outcomes—on average, women offered the program started childbearing later. Men’s improved labor market outcomes seem to be driven by improved educational outcomes.

Labor markets: One decade later, participants offered the program when they were younger had higher labor market participation and earnings than participants offered the program when they were older. Men offered the program when they were younger were more likely to have worked off their farm, to have recently migrated temporarily for work, to have had a non-agricultural salaried job, and to have had an urban wage job than men offered the program when they were older. Women offered the program earlier were more likely to have worked off the family farm and to have recently migrated temporarily for work.

Education: Men offered the program earlier had better education and learning outcomes on average than men offered the program later—men offered the program attended school for longer, were more likely to still be in school, and had higher learning levels. On the other hand, women had similar education and learning outcomes regardless of when they were offered the program. Women offered the program later were able to catch up to their peers who were offered the program earlier on most education and learning outcomes. This is likely because, relative to men, women offered the program later were more likely to still be in school by the time the program reached them.

Reproductive health: Childhood nutrition has important impacts on reproductive health, including the timing of puberty. On average, women offered the program when they were younger reached sexual maturity later and were less likely to be sexually active at age fifteen than women offered the program when they were older. On average, women offered the program when they were older had their first children earlier than women offered the program when they were younger. The researchers suggest that improved labor market outcomes for women offered the program when they were younger were driven by differences in fertility, as parenthood prevents women from participating more fully in the labor market.

The researchers note that CCTs to low-income families with low education levels could be an effective way of disrupting intergenerational poverty, both through human capital accumulation and by delaying childbearing for women.