The Effect of Vocational Training on Gender Norms in Northern Nigeria

- Job seekers

- Youth

- Adults

- Families and households

- Earnings and income

- Employment

- Empowerment

- Gender attitudes and norms

- Training

- Vocational training (TVET)

Women often face restrictive gender norms that limit their opportunities and slow down economic progress, but directly addressing those norms can provoke backlash in conservative settings. Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to test whether a gender-neutral job training could shift norms in a religiously conservative region of Nigeria. Youth who were offered job training earned more, broadened their friend groups, and adopted more progressive views on women’s education, labor force participation, and household decision-making. Caregivers of participants also improved their gender beliefs.

Problema de política pública

Gender inequality is a major and persistent challenge to economic development and well-being. Globally, women earn 20 percent less than men on average, and are less likely to participate in the labor force or hold decision-making roles. Family members, religious leaders, and community expectations often uphold restrictive gender norms that limit women’s autonomy in education, employment, and household decisions. These restrictions, in turn, contribute to lower female labor force participation.

Programs that aim to shift gender norms often address gender directly, but this can trigger backlash in conservative settings. While job training programs are typically designed to improve employment outcomes, their effects on gender norms are less understood. Emerging evidence suggests that such programs can influence outcomes beyond the labor market, like reducing crime recidivism by helping participants build skills, access employment, and strengthen social ties that promote stability and reduce risky behaviors. Can job training also shift gender attitudes in a similar way, by exposing participants to new people and beliefs at their workplaces?

Contexto de la evaluación

In Kaduna and Katsina, two states in Northern Nigeria, many women are held back from making their own choices about education, employment, and mobility because of strict gender norms and a conservative interpretation of Islam. Both states have been under Sharia law since the early 2000s. Women often face restrictions under the practice of kulle (seclusion), which in its strictest form prohibits married women from interacting with non-family members of the opposite sex. These norms are reflected in attitudes among youth: 77 percent of the study sample said that husbands should decide whether wives are allowed to work outside the home.

Girls also face pressure to marry and have children early. At age 20, 41 percent of women in the study were married, compared to just 1 percent of men. 55 percent of caregivers believed that husbands alone should decide whether the couple has children. Fathers of unmarried girls often have the final say over decisions about education, training, and employment.

These gender norms contribute to low levels of female labor force participation and social empowerment, which in turn are linked to high poverty rates. In Kaduna and Katsina, 74 and 66 percent of people live under US$1 per day, respectively. Unemployment rates in both states exceed 25 percent.

Detalles de la intervención

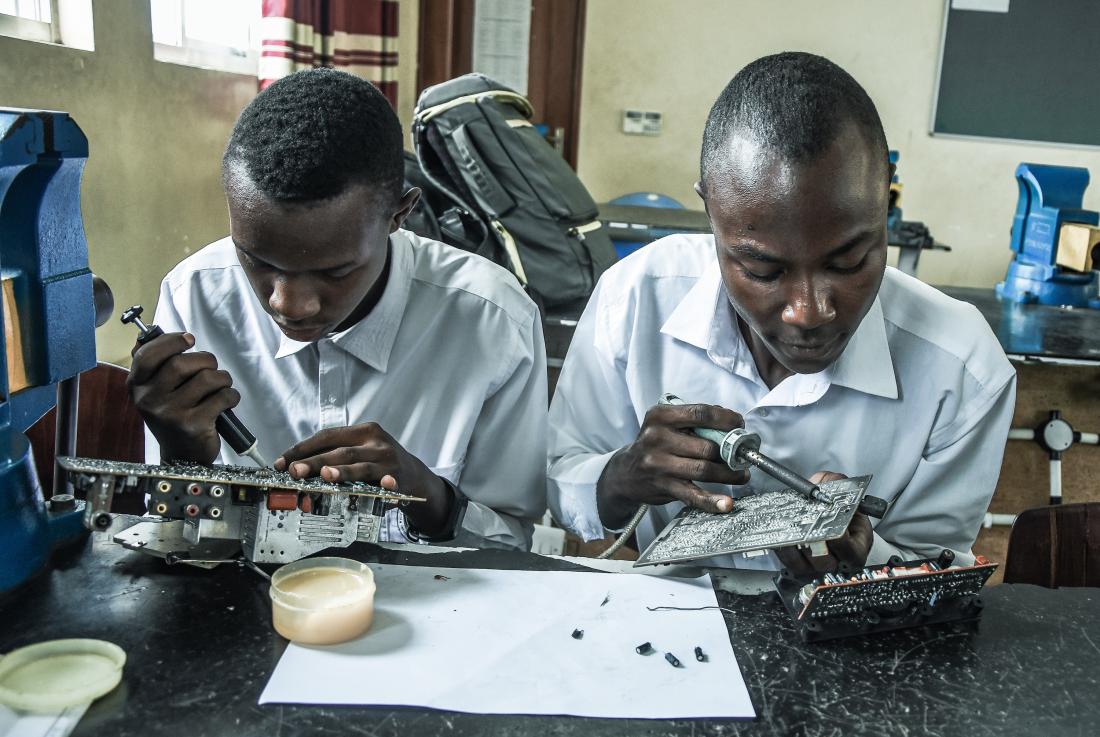

From 2015 to 2020, Adam Smith International ran the Mafita program in Northern Nigeria to help marginalized youth access skilled work or self-employment. Mafita included outreach, mentoring, support services, as well as a vocational training program known as the Community Skills Development Centers (COSDEC) program. In partnership with the Nigerian National Board for Technical Education, Mafita designed a locally relevant COSDEC curriculum. COSDEC targeted low-income youth aged 15 to 24, including early school leavers, orphans and vulnerable children, persons with disabilities, and those with limited access to formal education. Training began with three months of foundational (literacy, numeracy, and basic science) and soft skills (goal-setting, interpersonal communication, etc.) followed by nine months of trade training in one of seven areas: Carpentry and Joinery, Electrical Installation, Fashion Design, Hospitality, Masonry, Office Management, and Welding and Fabrication.

Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation in Northern Nigeria to test the impact of providing a gender-neutral job training to marginalized youth on their gender norms by expanding their economic opportunities.

The training took place in six different centers in Kaduna and Katsina, with a total of 1,824 participants. Participants applied to a specific trade training at their local center. Researchers then randomly selected 900 applicants from the different center-trade applicant pools to be offered the training, known as the intervention group. Some intervention group participants also engaged in an additional two-month training in entrepreneurship and business administration. The remaining 924 participants were assigned to the comparison group, did not receive any training, and were not allowed to apply to a different trade or center for the duration of the study. The evaluation ran from April 2017 to March 2018, with 73 percent of participants in the intervention group completing the program; researchers measured outcomes nine to fourteen months later.

Researchers measured youth gender norms through an index that combined survey responses around household decision-making, women’s equality and role in society, and domestic violence. They measured caregiver gender norms through a similar index that included female labor force participation and excluded domestic violence. Researchers also measured economic outcomes through the income and employment index which combined indicators on wage employment status, days worked, and monthly earnings.

Resultados y lecciones de la política pública

Youth who were offered job training adopted more progressive gender views, even though the training did not discuss gender. Their caregivers also became more supportive of women’s roles in work and decision-making. Evidence suggests that job training helped youth from conservative communities enter the labor market and build new social connections, which fostered more progressive gender views.

Labor Market Success: Youth who were offered training were 4.2 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to 10.9 percent employment among their peers (a 39 percent increase). They were also 13.7 percentage points more likely to be self-employed, from a base of 38 percent. Youth in the training group also earned ₦403 (USD 1.3) more per month than the comparison group (a 54 percent increase from a baseline of ₦752 (USD 2.5). Evidence indicates that labor market success explains about 20 percent of the shift in gender norms after the training. Researchers suggest that when youth secured jobs following the training, they observed women succeeding in the workplace and encountered new beliefs through interactions with coworkers, customers and bosses.

Social interaction: Youth who were offered training broadened their social interactions without losing existing connections or altering religious beliefs. They had 0.013 more friends of the opposite gender (a 29 percent increase from 0.045 in the comparison group). They also had, on average, 0.12 more friends from outside their neighborhood (a 10 percent increase from 1.2) and 0.27 more friends who were employed (a 10 percent increase from 2.8). Although trained youth did not report more friends from other religions or any new opinions on religious enforcement, they reported greater trust in leaders and people of other religions. These shifts in social interaction appear to be a key mechanism through which economic gains led to changes in gender attitudes: broader social networks were associated with more progressive views on women’s roles in society and household decision-making.

Youths’ Gender norms: As a result of the training, youth adopted more equitable views on household decision-making norms and women’s role in society. For example, youth who were offered training were 8.8 percentage points more likely to believe boys should do as much domestic work as girls (a 31 percent increase from 28 percent). Similarly, trained youth were 6.2 percentage points more likely to believe girls should speak as much as boys in class, a 14 percent increase from 45 percent in the comparison group.

Caregivers’ gender attitudes: Caregivers of participants also showed improved gender attitudes. For example, the belief that women should occupy leadership positions in society increased by 6.5 percentage points from a baseline of 85 percent, an 8 percent increase. Similarly, the belief that girls should speak as much as boys in class rose by 6.9 percentage points from a baseline of 75 percent, a 9 percent increase. These effects were particularly strong for caregivers with a female dependent enrolled in the study.

Vocational training can be a powerful tool not only for improving economic livelihoods but also for shifting gender beliefs in conservative societies, even when the curriculum does not directly address gender inequity.

Crost, Benjamin, Oeindrila Dube, Marcus Holmlund, Eric Mvukiyehe, and Emily Crawford. "Can Economics Opportunities Reshape Gender Norms among Religious Youth? Evidence from Northern Nigeria." Under review.