Low-income Americans are missing out on the public benefits they're eligible for. Simple interventions can help.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—often referred to as food stamps—is one of the largest social safety net programs in the United States. But every year thousands of households eligible for SNAP benefits do not enroll, missing out on food assistance that could be critical. Enrollment among adults over the age of 60 is particularly low; in 2012, nearly half of older adults who qualified to receive SNAP benefits did not enroll.

Why don’t more older adults apply for SNAP benefits—are they not aware of their eligibility? Is the application process too confusing or time-consuming? Or are they simply not interested? And how can organizations help more older adults access the SNAP benefits they are eligible for?

To investigate these questions, Amy Finkelstein (Co-Scientific Director of J-PAL North America) and I partnered with Benefits Data Trust (BDT), a national nonprofit committed to transforming how individuals in need access public benefits, to conduct a randomized evaluation.

In our evaluation, we wanted to test how different strategies designed to reduce barriers to enrollment might impact the number of older adults who apply for SNAP.

We worked with BDT and the Pennsylvania state government to randomly select 30,000 study participants from administrative records of low-income individuals. These individuals were not enrolled in SNAP, but we knew they were likely eligible because they were already enrolled in Medicaid, which has similar eligibility requirements in Pennsylvania.

Individuals in our study were able to apply for SNAP benefits at any time. Our research design was different from many other randomized evaluations, where one group receives program services and another doesn’t. We would not want to—nor would we be able to—prevent individuals in the comparison group from enrolling in a program they are legally entitled to, such as SNAP.

Instead, we used an approach called an encouragement design. We randomly assigned participants into three equal groups; participants in two groups received additional encouragement and support to enroll in SNAP, while those in a comparison group still had access to SNAP but received no extra encouragement.

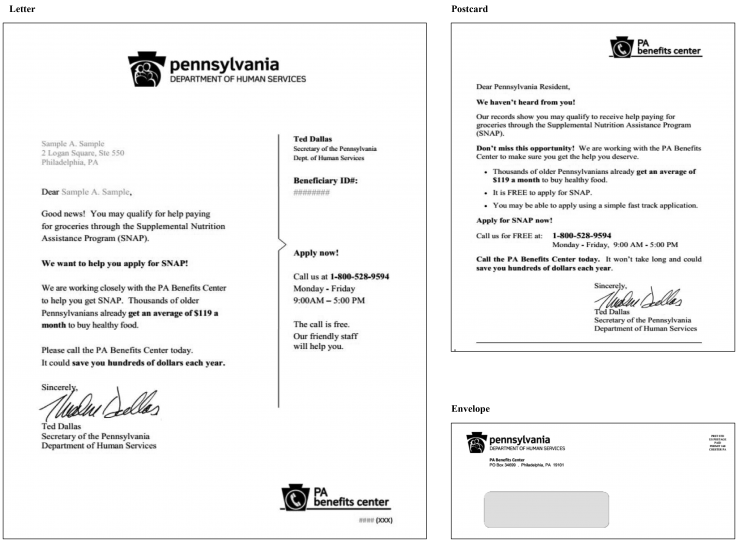

In our “Information only” group of eligible older adults, we mailed them a letter which informed them of their likely eligibility for SNAP benefits and provided a DHS (government) phone number to call to receive an application form. A randomly selected subgroup also received a follow-up reminder postcard eight weeks later if they hadn’t yet called.

In our “Information plus assistance” group, participants received the same outreach materials in the mail as the other group did. But their letter included a phone number that would connect them with our partner, BDT, instead of directly to DHS. If they called this number, they received extra assistance from a specialist who helped them submit an application and compile required documents, and answered any follow-up questions.

What did we find?

About 6 percent of study participants in the comparison group, who did not receive any additional encouragement, enrolled in SNAP over the nine-month study period. Participants who received the “information only” intervention (letters and a DHS phone number) were almost twice as likely to enroll. And among participants who received the “information plus assistance” intervention, enrollment rates tripled to 18 percent.

Just within our study sample, this intervention helped roughly 1,700 seniors access the food benefits that they need. If scaled up further, BDT’s intervention could help many more.

The findings suggest that lack of information about eligibility and challenges in navigating the application process prevent many older adults from successfully applying for and enrolling in SNAP benefits for which they are eligible. Our results also indicate that for some people, providing information about eligibility is enough to encourage them to enroll. But for many others, more intensive assistance is required to substantially increase enrollment. Overall, we think encouraging eligible people to enroll in SNAP seems like a relatively low-cost way to reach this low-income population.

To read about our study in greater detail, please see our recently released working paper (Take-up and targeting: Experimental evidence from SNAP), which provides more detailed results and includes a framework to analyze the overall cost and welfare implications of the interventions.