Workplace interventions to improve worker well-being

Summary

Policymakers often view decent jobs that offer fair income, stable employment, and opportunities for growth as an important strategy for lifting workers out of poverty. But access to such jobs remains limited. Workers in many parts of the world also endure harsh working conditions. According to a 2023 report by the International Labour Organization, nearly three million workers die each year from work-related diseases and accidents.1 Low pay and limited opportunities for skill development make it hard for workers to advance, while discrimination and workplace harassment—especially against women—can push people out of the workforce.

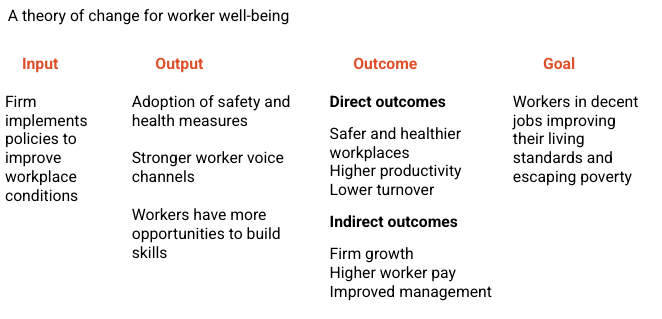

In this insight, worker well-being includes safety, health, mental well-being, empowerment, fair compensation, and opportunities for professional growth. To improve these areas, firms and researchers have tested workplace interventions such as better safety measures, stronger worker voice, and skill training. These efforts can also boost worker productivity, potentially leading to higher wages. However, the benefits workers receive depend on whether companies share productivity gains or whether workers can switch jobs for better pay. The theory of change below provides an abstracted visual guide for how improving workplace conditions can benefit both employees and firms.

A review of fifteen randomized evaluations and six quasi-experimental studies found that these interventions made jobs safer, improved job satisfaction, and helped workers build skills. The interventions also tended to be low cost to the firms and sometimes increased worker productivity. However, evidence that these productivity gains translated to higher pay for workers remains weak.

Supporting evidence

Workplace interventions addressing safety hazards and other health concerns have led to safer, healthier, and more productive workplaces. Several evaluations suggest that firms can be responsive to external demand for measures to improve worker well-being. In one study, multinational apparel firms enforced the creation of safety and health committees among their suppliers in Bangladesh, leading to better safety checklist performance by 0.23 standard deviations [1]. A quasi-experimental study found that Myanmar-based firms that exported to the European Union and the United States demonstrated better fire safety and health protocols relative to other local firms that sold domestically [2]. Managers of these firms noted that they had to pass third-party compliance audits to maintain their business ties, providing suggestive evidence that supply chain pressures can play an important role in workplace safety. However, external pressure alone may be insufficient to improve worker well-being. In the Bangladesh evaluation, enhanced safety measures were mainly seen in well-managed firms with strong worker-manager communication, suggesting that managerial capacity is crucial for effective implementation of safety measures [1].

Health-focused interventions may also enable workers to become more productive, as health can alter people’s cognitive function and job performance. Three randomized evaluations and four quasi-experimental studies showed that low-cost strategies to mitigate physical and mental strains on workers can result in increased productivity. These included using LED lights to reduce workplace temperatures [3], lowering excessive noise from manufacturing equipment [4], encouraging short afternoon naps at work [5], and paying wages in advance to alleviate stress associated with financial insecurity [6][7]. Higher levels of pollution were also found to result in lower productivity, suggesting that reducing workers’ exposure to poor air quality can benefit both them and the firm [8][9][10]. One randomized evaluation in Bangladesh found that providing access to free sanitary pads improved women workers’ health outcomes by decreasing the likelihood of urinary tract infections by 5.5 percentage points (or 42 percent), but it did not experimentally evaluate impacts on productivity [11]. Future research should explore the link between health outcomes and productivity.

Providing workers better opportunities to voice their concerns improved their job satisfaction, in some cases leading to increased productivity and retention. This finding was consistent across four randomized evaluations [12][13][14][15]. Strengthening worker voice channels such as providing feedback surveys and worker representation in executive groups can empower workers to contribute to improvements in their workplace conditions and culture. In China, a firm provided employees the opportunity to evaluate their managers. As a result, managers became more supportive and less critical toward their teams, and employees reported being happier. Employees also performed 2.3 percent higher on team-level key performance indicators [13]. Also in China, supervisors invited open discussion from workers, leading to a 10.6 percent productivity boost and 10.3 percent higher retention after twelve weeks, compared to workers who received lectures from their supervisors instead [15]. Workers may also inherently value the ability to share their feedback. In India, employees who completed a survey following an unsatisfying wage hike were 0.23 percentage points (or 20 percent) less likely to quit despite managers not yet taking action on the survey results [12].

Unions and other forms of collective action may provide workers with a valuable means of advocating for favorable workplace changes. However, there is a lack of research assessing how those efforts impact worker well-being. Exploring this relationship is an important area that warrants the attention of future studies.

Providing access to on-the-job skills training enabled workers and managers to strengthen their skillsets, yielding returns to the firms. Developing skills often helps people access better job opportunities and improve economic prospects, and thus it is an important facet of worker well-being. However, people may be constrained from growing their skills due to weak education systems or a lack of training opportunities. Three studies found positive impacts of on-the-job soft skills training for staff in garment manufacturing firms [16][17][18]. In one of these evaluations, female production line workers within a large garment manufacturer in India participated in a soft skills training program. Several months later, the trained workers showed greater teamwork and collaboration skills and were 4.7 percentage points more likely to have been promoted (a 3.5 percent rise over the comparison group). Moreover, trained workers were 16 percentage points, or 63 percent, more likely than their comparison group peers to request further skill development training, suggesting that workplace training can both be empowering for workers and open up additional opportunities for productivity gains to the firm [16]. In the other two evaluations, soft skills training for managers also led to higher productivity on their lines [17][18].

Although training programs and other skills development programs can be costly, firms should recognize that they can also be worthwhile investments that empower employees and potentially boost productivity. In the previously mentioned evaluation, total costs per participant were around US$94. Enhanced teamwork and collaboration enabled the trained workers to increase their productivity by an average of 7.4 percentage points, or 13.5 percent, compared to those who did not receive training. Researchers estimated that eight months after the training, these productivity gains resulted in net returns of 256 percent for the firm. In the other evaluation at the same manufacturer, managers were randomly assigned to receive soft skills training. Six months after the training, productivity gains from the manager training were estimated to be 54 times the cost [17].

Workplace interventions targeted at women, such as safer grievance reporting mechanisms, deliberate promotions, and on-the-job skills training, enabled them to tackle gender-specific barriers at work. In Bangladesh, safer harassment reporting surveys empowered women to report workplace abuse of physical harassment by 290 percent more and sexual harassment by 271 percent more, from baseline rates of 1.5 and 1.8 percent, respectively [19]. Another evaluation in Bangladesh found that deliberate promotions of women to supervisory roles challenged discriminatory beliefs, showing no loss in productivity [20]. Last, the aforementioned evaluation of soft-skills training in India demonstrated the value of investing in women and unlocking their skill potential [16]. Firm managers should recognize that both women and the business stand to benefit strongly from these inclusive practices.

Improved productivity does not guarantee higher pay for workers. More research is needed to understand under what conditions workers can capture more of the benefits that they create for their firms. The theory of change outlined above posits that higher productivity is associated with higher pay. This was the case in one study, where managers in an Indian garment factory who received soft skills training increased their teams’ productivity by 5.8 percent and their wages increased by 6 percent [17].

However, evidence also suggests that firms may not always offer higher pay to workers in response to improving their productivity, especially for lower-level workers. In the same Indian garment factory, despite female production line workers increasing their productivity by 13.5 percent after receiving soft skills training and having a higher likelihood of earning a promotion in title, their wages did not rise [16]. To explain why line workers missed out on raises while managers received them, researchers noted that lower-level workers likely had a harder time signaling their soft skills to other employers, reducing their likelihood of finding an outside offer. In some cases, workers can react to perceived unfair compensation by lowering their productivity or quitting [21]. Future research should answer questions around how workers can share more of the gains from their productivity and earn better wages.

ILO (International Labour Organization). “Nearly 3 Million People Die of Work-Related Accidents and Diseases.” November 26, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/nearly-3-million-people-die-work-related-accidents-and-diseases.

Boudreau, Laura. 2024. “Multinational Enforcement of Labor Law: Experimental Evidence on Strengthening Occupational Safety and Health Committees.” Econometrica 92, no. 4. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Tanaka, Mari. 2020. “Exporting Sweatshops? Evidence from Myanmar.” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 3: 442–456. Research Paper

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Namrata Kala, and Anant Nyshadham. 2020. “The Light and the Heat: Productivity Co-Benefits of Energy-Saving Technology.” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 4: 779–792. Research Paper

Dean, Joshua T. 2024. “Noise, Cognitive Function, and Worker Productivity.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16, no. 4: 322–360. Research Paper

Bessone, Pedro, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, Heather Schofield, and Mattie Toma. 2021. “The Economic Consequences of Increasing Sleep Among the Urban Poor.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 136, no. 3: 1887–1941. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Kaur, Supreet, Sendhil Mullainathan, Suanna Oh, and Frank Schilbach. 2024. “Do Financial Concerns Make Workers Less Productive?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 140, no. 1: 635–689. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Sowmya Dhanaraj, Anant Nyshadham, Smit Gade, and Apoorv Somanchi. “The Impacts of Earned Wage Access on Low-Income Women Workers.” Working Paper, February 2025. Research Paper

Graff Zivin, Joshua, and Matthew Neidell. 2012. “The Impact of Pollution on Worker Productivity.” American Economic Review 102, no. 7: 3652–3673. Research Paper

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Namrata Kala, and Anant Nyshadham. 2022. “Management and Shocks to Worker Productivity.” Journal of Political Economy 130, no. 1: 1–47. Research Paper

Chang, Tom Y., Joshua Graff Zivin, Tal Gross, and Matthew Neidell. 2019. “The Effect of Pollution on Worker Productivity: Evidence from Call Center Workers in China.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 1: 151–172. Research Paper

Czura, Kristina, Andreas Menzel, and Martina Miotto. 2024. “Improved Menstrual Health and the Workplace: An RCT with Female Bangladeshi Garment Workers.” Journal of Development Economics 166 (January): 103174. Research Paper

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Teresa Molina, and Anant Nyshadham. 2022. “Expectations, Wage Hikes and Worker Voice.” The Economic Journal 132, no. 645: 1978–1993. Research Paper

Cai, Jing, and Shing-Yi Wang. 2022. “Improving Management Through Worker Evaluations: Evidence from Auto Manufacturing.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 137, no. 4: 2459–2497. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Smit Gade, Teresa Molina, and Anant Nyshadham. “Sotto Voce: The Impacts of Technology to Enhance Worker Voice.” Working Paper, September 2022. Research Paper

Wu, Sherry Jueyu, and Elizabeth Levy Paluck. 2025. “Having a Voice in Your Group: Increasing Productivity Through Group Participation” Behavioural Public Policy 9, no. 1: 192–211. Research Paper

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Namrata Kala, and Anant Nyshadham. 2023. “Returns to on-the-Job Soft Skills Training.” Journal of Political Economy 131, no. 8: 2165–2208. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Adhvaryu, Achyuta, Emir Murathanoglu, and Anant Nyshadham. “On the Allocation and Impacts of Managerial Training.” Working Paper, June 2023. Research Paper

López-Peña, Paula, Muhammad Kamruzzaman Mozumder, Atonu Rabbani, and Cristopher Woodruff. “Toxic Managers, Firm Productivity, and Worker Well-Being: Evidence from Bangladeshi Garment Factories.” Working Paper, January 2025. Research Paper

Boudreau, Laura, Sylvain Chassang, Ada Gonzalez-Torres, and Rachel M. Heath. “Monitoring Harassment in Organizations.” Working Paper, December 2024. Research Paper

Macchiavello, Rocco, Andreas Menzel, Atonu Rabbani, and Christopher Woodruff. “Promoting Women to Managerial Roles in the Bangladeshi Garment Sector.” Working Paper, October 2024. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Coviello, Decio, Erika Deserranno, and Nicola Persico. 2022. “Counterproductive Worker Behavior After a Pay Cut.” Journal of the European Economic Association 20, no. 1: 222–263. Research Paper