Building research partnerships to address the opioid crisis in Minnesota, part two

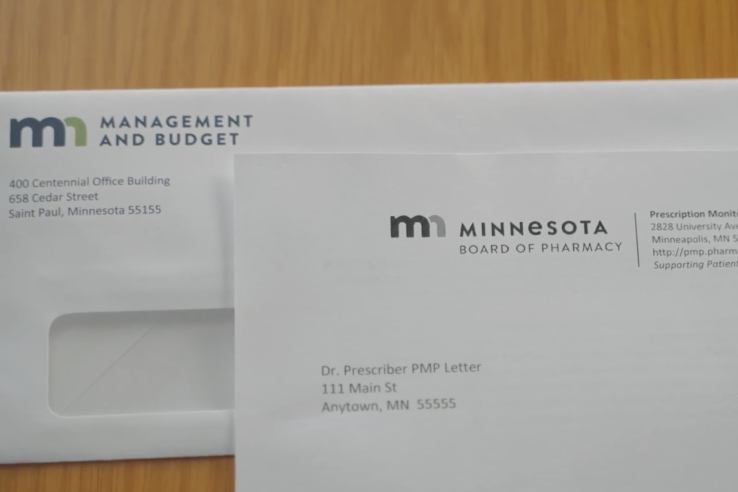

Mireille Jacobson (University of Southern California), Weston Merrick (Minnesota Management and Budget or MMB), and Adam Sacarny (Columbia University) sit down with J-PAL staff to discuss their recent paper in Health Affairs. The paper reports on the results of their randomized evaluation assessing how various letters affected physicians’ use of Minnesota’s prescription monitoring program (PMP). The PMP is an electronic database that tracks controlled substance prescriptions in the state. They discuss the results, broader implications, and future opportunities for evaluation.

This evaluation was awarded funding and technical support through J-PAL North America’s State and Local Evaluation Incubator and received Research Management Support. In part one of this blog series, published in the summer of 2021, Weston and Adam discussed their research partnership and the development of the study.

What were the key outcomes or results of the study?

Adam: The first main outcome was whether the clinicians in the study searched the prescription monitoring program (PMP). On this outcome, we see pretty substantial and durable effects. Search rates rose by about four percentage points from the most effective letters, and that effect lasted at least eight months.

The second outcome was whether the clinicians changed their co-prescribing of opioids with two other classes of medications, benzodiazepines and gabapentinoids. We focus on co-prescribing because these drug classes have interactions with opioids that can increase the risk of overdose. We don't detect any effects there, which probably reflects that prescribing is a lot harder to change than PMP use.

Mireille: We also saw that some clinicians who received letters made new PMP accounts, as they didn’t previously even have an account, even though they should have been searching the PMP based on both the law in the state and the best clinical practice. So these letters brought a hard-to-reach population into using the PMP who may not have otherwise engaged with it.

What are the broader implications of the results?

Adam: Every state has or is setting up a PMP, but the effects of these programs from recent meta-analyses look a bit disappointing. One of the reasons might be that many clinicians don't use them. What our study shows is that simple letters can move the needle on clinician engagement with PMPs. As a result, these letters could be of interest to other PMPs or even healthcare organizations that want to get their clinicians to use the PMP.

In addition, while changing prescribing with letters seems to be more difficult, getting clinicians to use the PMP could still be useful because it could help clinicians become better informed about their prescribing. They then have a reason to inform patients about the risks that they might face from taking these prescriptions, like overdose, and tell them about naloxone, the overdose reversal medication.

How are these results informing future policy choices?

Weston: The Minnesota Board of Pharmacy was an extremely engaged partner in this work. They care a lot about making sure that the PMP is an effective system for providers to use. They used the results of this study to create and inform some automated messages sent through the PMP, using the behavioral lessons we used in this study.

The Board of Pharmacy is also very interested in looking at further interventions to increase the likelihood that folks are using the PMP and using it correctly to prescribe in a safe way.

More generally, we've started to realize that these nudge messages are about improving the customer experience of accessing the government. There's a reason why these prescribers aren’t using the PMP— maybe they don't know about it, maybe they don't know how to sign up, maybe they forgot their login, whatever it may be. This simple letter was able to prompt them to better use a service that was available to them. This is just one example of how we can continue working to improve access to, and use of, government services across the state.

Are you considering future collaborations in this partnership?

Adam: We’re certainly trying to build on these successes and use the groundwork already laid to launch new projects. I’m hoping we can work on interventions that not only try to stop risky prescribing but try to promote beneficial care. Weston and I and our collaborators have been talking and trying to think about both sides of the issue—not only reducing bad things but also increasing good things—and how nudge-type interventions can be useful there.

Mireille: Yes—and all of these strategies are fundamentally about trying to mitigate the harms of the opioid epidemic, from every angle possible, whether through better prescribing or better access to treatment.

Weston, more generally, how has this partnership impacted the ways you and your team think about the role of evidence?

Weston: This project was a really important example of a research partnership that worked really well. We were able to leverage outside resources and expertise to identify a meaningful policy question, use our existing data to answer that question, change policy, and then publish results in a journal so that places outside of Minnesota can learn from our experience. Having that kind of example allows us to go back to state leaders and say “this is why we should do an evaluation, and this is what you’ll get back,” which makes it much easier to start future projects that can meaningfully impact the health and well-being of Minnesotans.

Any last thoughts?

Weston: I'll just end on the fact that we're so grateful to the Board of Pharmacy and PMP staff to endeavor on this project with us. They've been a really wonderful partner and we’re hoping to work with them more on future projects.

Adam: I would second that—we are really grateful that the PMP was willing to devote their time to this rigorous evaluation.

Mireille: I also want to emphasize that it was invaluable to have active collaborators, like Weston and Ian Williamson, who work in the government. They were able to help manage the implementation process given their knowledge of organizational constraints but, more importantly, were able to help design and implement a project that is relevant not only for academia but also for policy.

This piece is part of an ongoing series highlighting research partnerships with state and local government agencies fostered through J-PAL North America’s State and Local Evaluation Incubator. The second & third pieces feature Shasta County's evaluation of text message reminders to reduce failure to appear in court.

Related Content

Building research partnerships to address the opioid crisis in Minnesota

Building research partnerships to address failures to appear for court in Shasta County, part one