Using evidence to shape climate policy: Five takeaways from J-PAL Europe’s policy roundtable in Bonn

How can we make climate policy more effective, equitable, and evidence-driven? That was the guiding question of J-PAL Europe’s recent policy roundtable in Bonn, Germany. The roundtable was hosted alongside the Institute of Labour Economics’ (IZA) Climate and Environmental Economics workshop and supported by J-PAL’s King Climate Action Initiative (K-CAI). It was moderated by Andre Zollinger (Senior Policy Manager, J-PAL), and brought together around eighty policymakers, researchers, funders, and private sector leaders.

The event focused on how organisations, from governments to implementing partners, can use rigorous evidence to shape smarter, more impactful climate policies. Panellists included Jan Minx (Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research), Kira Vinke (German Council on Foreign Relations), Lucy Yu (Centre for Net Zero), and Markus Steinich (GIZ), who shared diverse experiences and ideas for bridging research and policymaking.

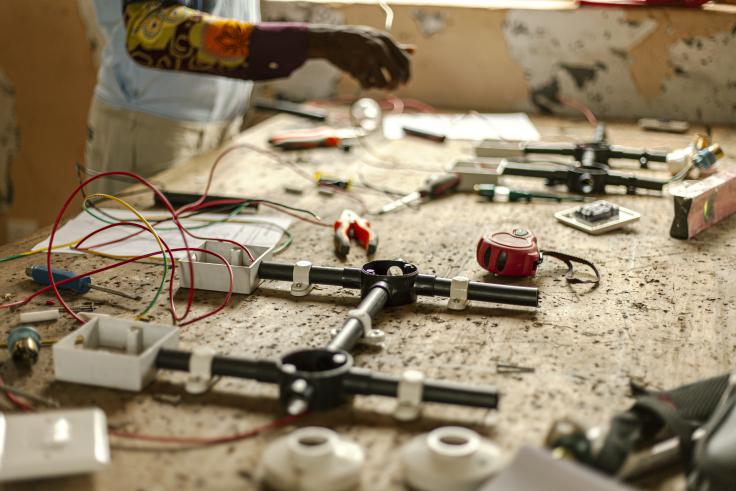

J-PAL Middle East and North Africa Executive Director Ahmed Elsayed opened the session with a case study on J-PAL’s Air and Water Labs with Community Jameel, which work closely with local governments in Egypt, India, and South Africa to co-design, test, and scale evidence-informed solutions to increase access to clean air and water. This model underscored the importance of cross-sector collaboration and embedding evidence directly into policy institutions.

Five takeaways for more evidence-informed climate policy

1. Ambition alone is not enough: we need to know what works.

Governments have set bold climate targets, but real progress requires rigorous evaluation to identify what delivers results in practice. Resources should be directed toward solutions shown to be effective and equitable, and away from those that are not. As a recent Nature Reviews Clean Technology article notes, even widely adopted interventions often lack strong evidence of effectiveness. Despite a growing interest in climate policy, robust, counterfactual-based evidence remains limited. Jan Minx informed the audience that, a decade after the Paris Agreement, targets were not being met, in part due to a lack of evidence on what works and insufficient funding for rigorous climate policy evaluation. He emphasised that technology development is well-funded, but evidence-informed policymaking lags.

2. Institutionalise evidence use locally.

The Air and Water Labs example showed the need to strengthen local institutions to run policy evaluations and adapt successful solutions: without local ownership and data capacity, even good ideas struggle to take root or scale effectively. In the same vein, Kira Vinke suggested engaging and empowering local actors such as NGOs and research institutes to ensure relevance and local ownership. Local embeddedness offers a promising path forward through the creation of local ecosystems in which governments, researchers, and civil society collaborate continuously, not one-off but for long-term impact. This approach is in line with J-PAL’s ambition to strengthen a localised, decentralised culture of evidence generation and use.

3. Communicate benefits clearly and persuasively.

Kira Vinke warned that political setbacks undermine trust and global collaboration, especially among and with lower-income countries. Lucy Yu also reminded the audience that evidence-informed solutions need strong public support. She further noted that some conventional understandings in climate and energy policy need to be revisited in the face of new evidence so that nuance can be communicated clearly.

Thus, Lucy Yu argued that low engagement with policy solutions often reflects poor user design rather than user failure. She explained how the Centre for Net Zero leverages electricity consumption data from over 10 million users across eight countries, to test behavioural and pricing interventions aimed at shifting energy demand. Their evaluation on installing rooftop solar and batteries in low-income households in the UK shows how targeted interventions can reduce grid reliance, lower bills, and even turn homes into net generators, helping meet both energy and equity goals. Another Centre for Net Zero evaluation, funded by J-PAL’s King Climate Action Initiative, explores automated electric vehicle charging tariffs to lower consumer costs and improve grid efficiency.

4. Evidence must be accessible, actionable, and alive.

Markus Steinich supported this claim and called for an iterative approach to evidence, based on testing, refining, and learning continuously to adapt to local needs and constraints. Given the powerful use of messaging through evidence, Lucy Yu further highlighted that evidence can be used to create space for new conversations with policymakers about incorporating demand-side flexibility and real-world consumer behaviour into models and policy design.

To further strengthen this, research should be packaged for different audiences, from senior officials to frontline practitioners. Jan Minx advocated for tools such as the upcoming World Bank’s Impact AI database to make research more interactive and usable. He also co-organises the What Works Summit, which brings together researchers, policymakers, funders, and advocates to build a more evidence-led climate action movement across the globe. Evidence is not static; it should evolve with feedback and changing realities. This further necessitated the need for regular dialogue and collaboration with non-academic actors for buy-in and real-world application.

5. Funding and timing gaps remain major barriers.

Evaluation takes time, money, and collaboration; things that are not always built into fast-moving policy cycles and in a time of tightening budgets. More flexible funding and better integration of research timelines into policymaking are critical. Even where evidence exists, uptake is often slow. Hence, there is a need for deeper, sustained engagement between researchers and policymakers, as well as the need for systems that can adapt in response to new insights.

Furthermore, all panellists agreed that oftentimes not enough information is available to calculate the “return on investment” of evidence use, even though cost-effectiveness is a major lever for overall policy effectiveness. They strongly supported the need to calculate such figures. For example, an interesting insight into lower costs was suggested by Lucy Yu, who saw promise in AI to improve long-term energy demand projections using only current data. Thus, Centre for Net Zero’s Faraday model combines AI with insights from randomised evaluations and industry stakeholders to forecast future energy demand. Lucy Yu also mentioned how some of their studies calculate the marginal value of public funds of different policy interventions for this exact reason.

How to get involved

The challenges of climate change require smart, tested, and scalable solutions. At J-PAL Europe, we are committed to supporting governments and organisations in building evidence-driven climate policies that reduce emissions and improve lives. J-PAL’s Environment, Energy, and Climate Change sector team supports rigorous research and policy engagement across a range of topics, from air pollution and clean energy to climate resilience and sustainable agriculture. Through initiatives like the King Climate Action Initiative, we are working with partners globally to co-create solutions that work.