Building an effective COVID-19 response: Expanding access to jobs and the social safety net

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on workers in the United States, leading jobless claims and unemployment rates to skyrocket. Not only does employment provide earnings, skills development, and ties to critical resources such as health insurance, but long-term unemployment is associated with sustained earnings loss, worse health outcomes, and negative intergenerational impacts on workers’ children.

Job and wage losses have disproportionately impacted low-income workers, workers of color, and women, setting the stage for pre-existing racial and gendered wealth and wage gaps to widen. The COVID-19 Recovery and Resilience Initiative aims to identify effective ways to support workers in the face of COVID-19 related job and wage loss by evaluating innovative strategies to boost income and employment and connect workers to social benefits.

Pre-existing inequities in labor markets

In 2019, 44 percent of all workers qualified as “low-wage,” defined as those who make below two-thirds of the median wages for full-time, full-year workers. These low-wage workers earn median hourly wages of $10.22 and median annual earnings of about $18,000, compared to the median hourly wage of $19.33 per hour for all US workers. Low wage occupations include retail sales workers, cooks and food preparation workers, construction workers, and motor vehicle operators. Many of these jobs provide limited opportunities for economic mobility.

Women of all races are overrepresented in low-wage jobs, but this is especially pronounced for women of color. Low-wage jobs in which women are over-represented include food preparation and service jobs, home health aides, child care workers, and cleaning or laundry professionals, among others. Further, Black and Hispanic women in low-wage jobs are more likely to be the primary breadwinners of their families and more likely to have household incomes near the poverty line relative to their white counterparts.

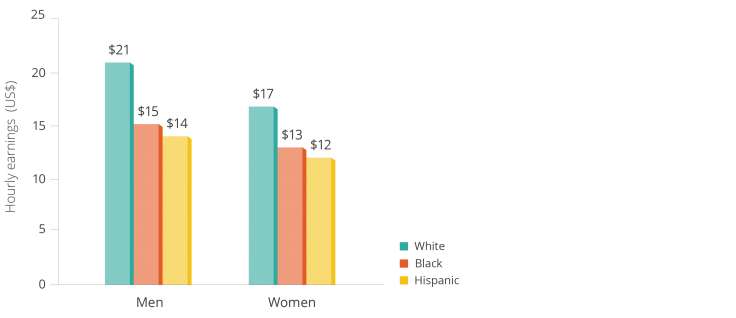

In addition to job segregation by gender, the United States is home to stubborn racial and gendered wage gaps (illustrated in Figure 1). Wage gaps persist when researchers control for educational attainment, pointing to discrimination in the job market.

Workers of color not only face lower wages but also higher unemployment rates than white workers, with the unemployment rate for Black workers historically hovering at or above double the unemployment rate for white workers. Many structural factors contribute to this gap, including the mass incarceration of Black men and racial bias in the hiring process. Hiring discrimination against people of color has been well documented in the experimental literature.

Additionally, when Black or Hispanic workers face job or wage loss, they are less likely than white workers to have savings to cover three months of expenses due to systems that have long limited communities of color from wealth accumulation and access to opportunity.

Lastly, labor market outcomes are closely tied to involvement in the criminal justice system. In the United States, Black and Latinx individuals are arrested, charged, and incarcerated at a higher rate than white individuals. People who have been incarcerated are nearly five times more likely to be unemployed than those who have never been incarcerated. Further, formerly incarcerated people of color and women face even greater barriers to employment despite being the most likely to look for jobs after returning home.

The Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 has resulted in massive job losses and has exacerbated existing racial and economic labor market disparities. By the end of May, over 40 million workers had filed initial jobless claims—meaning that they are new, not continuing, claimants for unemployment benefits—since the beginning of the U.S. pandemic in mid-March.

Though employment numbers have improved slightly, more than 28 million people were receiving some form of unemployment benefits on August 1, and the number of people applying for first-time unemployment insurance continues to hover at around 900,000 per week in early September.

These numbers do not include people who have lost their jobs but have not filed for unemployment, those who have left the labor force by not continuing to look for work, new graduates who have not found work, those who have lost work in the informal labor market, or undocumented immigrants who have lost their jobs but are not eligible for benefits.

Many businesses that implemented temporary lay-offs in the early stages of the pandemic are now shifting to permanent cuts of their employees, and over 100,000 small businesses have closed for good. Construction, leisure and hospitality, and manufacturing are among the major industries hit hardest by COVID-19 unemployment, all of which employ relatively high shares of low-wage workers.

Consequently, low-income workers have faced the highest rates of job loss. As of late July, more than two-thirds of workers earning a salary of less than $25,000 before the pandemic were out of a job—a number that has continued to rise even as higher-wage sectors have shown signs of recovery.

Over half of all lower-income adults say they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut due to COVID-19. These job and income losses have contributed to increased hardships such as difficulty making housing payments and food insecurity. Many low-income workers are being pushed to draw from limited savings, if available, or take on debt.

The labor market impacts of COVID-19 differ by race. Black and Hispanic workers have faced higher overall rates of unemployment and slower jobs recovery than white workers during the pandemic. Even as job numbers for white workers began to improve in May, Hispanic workers experienced much smaller job gains while unemployment for Black workers continued to rise.

Black and Hispanic workers who were not laid off are more likely to be in frontline and service jobs that increase their exposure to the virus, and more likely to rely on public transportation for jobs that cannot be done from home. This reality has likely contributed to racial disparities in the health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 related job losses have also been gendered. Because of the persistence of job segregation by gender in the labor force, women are more likely to work in jobs eliminated by the pandemic, such those in the restaurant, leisure, and hospitality industries. In May, the unemployment rate for women was two points higher than for men, with Black and Hispanic women facing particularly high joblessness rates.

As noted above, these rates do not account for job losses in the informal labor market, such as the major job losses faced by domestic workers, over 90 percent of whom are women and most of whom are women of color.

Women who remain employed are more likely than men to have work that exposes them to the coronavirus. Further, if day-care centers and schools cannot safely reopen, many women will be unable to reenter the labor force due to the need for child care, as child care duties often fall on women rather than men.

This unequal distribution of child care expectations is exacerbated by the fact that men tend to be paid more than women. Child care closures will disproportionately harm women of color both as child care providers and as working mothers struggling to access care. Further, women who leave work to care for children are no longer considered to be “in the labor force” and will therefore not be reflected in unemployment numbers.

Research to Support Workers

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused massive economic hardship for millions of workers, and exacerbated pre-existing racial and gendered economic disparities. As the United States faces unemployment and sectoral reallocation on a massive scale, new research can identify effective strategies to connect workers to jobs, keep individuals tied to benefits, and train workers to succeed in new industries.

How can policymakers support those who are unemployed?

One method to support individuals who are unemployed is to ensure access to financial resources to replace lost income. New research can prioritize projects that expand access to social benefits or monetary support for unemployed individuals. Potential important studies may include evaluations of unconditional cash transfers or informational campaigns to ensure tax credit or benefits take-up by eligible individuals, especially when governments grapple with unprecedented demand

Another risk of unemployment in the United States is a loss of health care coverage. To help workers retain health coverage, new research can explore the impact of portable benefits programs that tie benefits to the person rather than to a job or develop interventions to smooth workers’ transition to health insurance through the Affordable Care Act.

What strategies can keep workers connected to employment?

Important questions exist around the short- and long- term impacts of new and different forms of unemployment, including partial unemployment and work sharing strategies that keep individuals connected to their jobs rather than entirely laid off. Such programs continue to provide workers with income, albeit decreased, and keep them connected to benefits.

Strategic employee sharing programs are also an innovative method to keep individuals connected to work in the face of layoffs. In such a program, employers collaborate to allocate their shared pool of similarly skilled workers to available opportunities. For instance, if one company has furloughed employees but another similar company has increased demand for workers, employee sharing programs can funnel furloughed workers directly into new opportunities.

New projects may also address strategies to support small business owners and enable small businesses to continue to employ staff. This may come in the form of financial training interventions or subsidized employment placements at small businesses. New interventions should also aim to support workers in informal sectors such as care or domestic work by identifying effective methods to compensate workers’ efforts.

What programs can improve the job-search process?

Re-employment will be a key element of economic recovery for families and communities in the face of the COVID-19 recession. New research can investigate effective methods to match job-seekers to available jobs and sectors that suit their skills, though these interventions should focus on connecting workers to quality jobs that support economic mobility. In-person counseling or technology-based job search platforms offer promising opportunities for matching.

Training programs may also play an important role in preparing workers for new positions in the workforce. Virtual reskilling programs can train workers on new skills who lost their jobs due to the pandemic. New research can work to identify effective training or sectoral employment programs that provide participants with valuable education and networking opportunities to shift careers.

As jobs are reallocated post COVID-19, where will opportunities for workers arise?

Researchers should work to understand what sectoral reallocation will look like following the immediate COVID-19 crisis. COVID-19 may reshape the landscape of the job market, particularly for workers in the service industry. Researchers should strive to understand where job opportunities will disappear and where new opportunities are arising. This understanding can shape sectoral employment and training programs to best prepare participants for success upon completion.

Individuals involved in the criminal justice system experience substantial barriers to participating in the labor market. As such, potential research questions to support criminal justice reform are included below.

How can communities effectively support individuals who have been released from incarceration?

Certain states and local jurisdictions are working to decrease the population of jails and prisons to lower the risk posed by COVID-19. Hundreds of people have been released from jails or prisons early with more releases scheduled.

As individuals are released, researchers can work with community organizations to identify effective strategies for successful re-entry. Further, coronavirus-related early releases present a unique opportunity for researchers to measure labor market and justice outcomes for people who were released early to inform long-term criminal justice reform efforts.

Do decarceration strategies adopted during the pandemic have positive outcomes in a post-pandemic setting?

To reduce crowding in jails and prisons during COVID-19, policymakers turned to policies such as the elimination of cash bail and adoption of early release for people convicted of low-level crimes or people held on bail. These policies have long been the demands of criminal justice reform advocates. The adoption of these policies during the pandemic presents researchers with a rare opportunity to evaluate them. Understanding the outcomes of such policies can inform policymakers’ decisions to scale up or modify such reforms after the COVID-19 crisis has resolved.

This post is an installation in J-PAL North America's "Building An Effective COVID-19 Response" research guide blog series. The complete series highlights the interaction between COVID-19, research, and the policy areas of jobs and the social safety net, health care delivery, and education.