Prepaid versus Postpaid Electricity: Provision, Access, and Efficiency

This post was originally published on African Arguments on May 19, 2022, and is part of an ongoing series. Read the other blogs in the series on preparing households for shocks through universal basic income; obstacles to accurately identifying those in need of social assistance; the benefits and challenges of digital IDs; and increasing girls’ enrollment in school.

This is also the first blog in our series on energy access. Read the second blog post on emerging evidence and policy lessons for balancing industrial growth, energy use, and climate change, and the third blog post on using evidence to address energy poverty in Europe.

While access to electricity is essential for economic development, it is still not a reality for many households in sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2019, only 47 percent of the sub-Saharan African population (and just 28 percent of the rural population) had access to electricity compared to 90 percent of the global population. The electricity supply also is often unreliable: around 78 percent of firms in Africa experienced electricity outages in 2020, compared to an average of 52 percent of firms globally.

Kerosene and biomass are commonly used for lighting and cooking across sub-Saharan Africa, especially in rural areas. When burned, these fuels emit black carbon, which can cause health problems when inhaled, and CO2 which contributes to climate change. Using electricity in place of these fuels for lighting reduces carbon emissions, especially in countries like Kenya, where the electric grid is mostly renewable and can support appliances like fans and refrigerators that may help households adapt to climate hazards.

Yet, in places where electricity is available, it is often unaffordable for consumers. It is estimated that unpaid electricity bills in sub-Saharan Africa amount to around 0.17 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for all nations across the region. For example, a randomized evaluation conducted in Cape Town showed that 24 percent of consumers in low-income neighborhoods have been disconnected by energy companies due to nonpayment. Additionally, 26 percent of customers have outstanding electricity bills, more than 50 percent of electricity bills are not paid on time, and 2 percent of monthly bills are never paid. Unpaid electricity bills cause households to accumulate debts that can be difficult to overcome. These debts also hinder national utilities’ ability to expand or improve upon energy grids, making it harder for the households they serve to access electricity.

In order to address these electricity supply debts, many countries in Africa are transitioning from postpaid to prepaid electricity metering, however, the way this transition will affect households is not well understood. What are the differences between the two billing systems, and how can they affect energy access?

Understanding electricity payment systems

In prepaid electricity systems, consumers pay their electricity bills beforehand, while in postpaid systems, consumers pay their electricity bills after consumption. Prepaid consumers are able to directly monitor the amount of energy they use through a customer interface unit composed of a keypad and a screen installed in their house and can only use as much energy as they have purchased. The customer interface unit is typically either integrated into the meter and installed in the house or split from the meter, which is installed in a secured location, only giving consumers access to the customer interface unit. Postpaid customers are usually unable to directly monitor their energy use and expenses and may end up using more energy than they can afford. Those who are unable to pay their bills on time fall into debt to the utilities. After a sometimes arbitrary number of missed payments, households may be disconnected and face steep fees for reconnection, which can keep them from accessing electricity services.

Is prepaid electricity a viable solution to energy access?

Overtaxing electric grids often results in widespread energy shortages. Blackouts are common across sub-Saharan Africa, especially in the evenings, leaving households without access to electric lighting during peak hours. Since prepaid customers have the opportunity to monitor their energy use through the consumer interface unit described previously, they may be less likely to overuse energy. Households using prepaid meters as part of the randomized evaluation in Cape Town reduced their average energy consumption by 14 percent. Insights from the evaluation in Cape Town are further supported by pre-post analyses of prepaid systems in South Africa and Nigeria that also suggested reductions in energy consumption, up to 50 percent in some cases. Additionally, a descriptive case study in Rwanda suggested that the energy lost during provision decreased from 26 percent to 18 percent after consumers switched to prepaid meters. Energy conservation encouraged by prepaid systems may reduce the frequency and severity of blackouts. For higher-income households in countries where electricity is generated using fossil fuels, this energy conservation would also lessen CO2 emissions. However, in contexts where higher energy consumption is necessary for economic growth, energy conservation may limit economic growth. In these contexts, policymakers may need to balance between pursuing climate goals through energy conservation and economic goals. Encouraging the development of energy-efficient technologies could potentially forward both goals.

One of the potential benefits of prepaid systems for consumers is that they can reduce debts owed to utility companies, since energy is purchased ahead of consumption and households do not face additional fees when energy is used. The majority of respondents to a survey conducted in Tanzania preferred prepaid over postpaid meters, as lessening debts offered them more financial freedom.

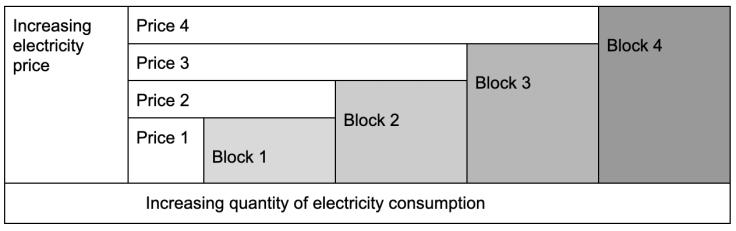

Despite reducing debts, households may still face disconnection under a prepaid system if they struggle to purchase on a regular basis due to fluctuations in income. The most common price scheme for prepaid electricity across sub-Saharan Africa is an ‘inclining block tariff’ (see Figure 1 below), where the price of each unit of electricity increases as more units are purchased. Under this price scheme, low-income consumers who do not have consistent wages may end up buying electricity at a higher price if the fear of not being able to make consistent payments leads them to purchase several monthly quantities of electricity consumption at once.

Additionally, while prepaid meters may encourage energy conservation among wealthy households, they may also encourage low-income households to underutilize the utilities, meaning that the benefits derived from appliance use would be limited. Consumers with intermittent income may ultimately return to using kerosene or biomass if they are unable to purchase electricity credits throughout the month. South Africa has tried to bolster energy consumption among low-income households with a free basic municipal services program, which provides low-income households 50 kWh of free electricity per month through prepaid meters, though some descriptive evidence suggests that improving how beneficiaries of free basic services programs are identified and enrolled may be needed to increase their reach.

Depending on the context, prepaid meters can be profitable to energy utilities. In Cape Town, the transition from postpaid to prepaid electricity led to better payment recovery, lower recovery costs, and earlier payments for the utility company, although consumers reduced their electricity consumption. If the total revenue gained through cost recovery by utilities that have transitioned to prepaid electricity surpasses the total revenue lost due to lower electricity consumption, they could use the net revenue gained to improve energy delivery and expand grids to rural communities that suffer from the lowest levels of energy access. However, the true effect on energy access would depend on how the utilities are regulated and what policies are in place to make sure households previously using postpaid meters can still afford energy.

Areas for future research

Switching from postpaid to prepaid electricity may prevent low-income consumers from becoming debtors to utility companies but may be less reliable for households with intermittent income. While studies suggest prepaid meters may help utilities expand and monitor the electric grid, there remains little rigorous evidence on how these systems affect households. More evidence on improving service regulation and protecting the needs of vulnerable consumers is needed to determine what role prepaid electricity can play in achieving universal energy access.