Increasing your visibility as a researcher

A strong online presence can be an important tool for building a network. It has the potential to increase your credibility, visibility, and enhance your reputation as a knowledgeable researcher in an international setting.

Credibility: You are who you say you are. A reliable digital footprint, highlighting your legitimacy as a researcher, may be important for research funding organizations in their selection process. Prior to granting funds, funding organizations may search online for the applicant to confirm the authenticity of the details provided by the applicant. Particularly for lesser known researchers, an online profile can be a supportive tool to reassure external reviewers of your credibility.

Visibility: In a growing digital world, an online presence has become more and more important. A strong online presence allows you to showcase your work and be visible to a broader audience. Curating an online presence with all your work in an easily accessible format can increase the likelihood that it will be read.

Reputation building: A strong online presence can be a good signal to those who are looking to connect with you. There may be interesting co-authors who are interested in collaborating with you (and vice versa); being more visible online may encourage potential co-authors to connect.

This is the first post in a two-part series compiling resources for early career researchers. Here, we focus on enhancing your online presence so that others can more easily learn about you and your work.

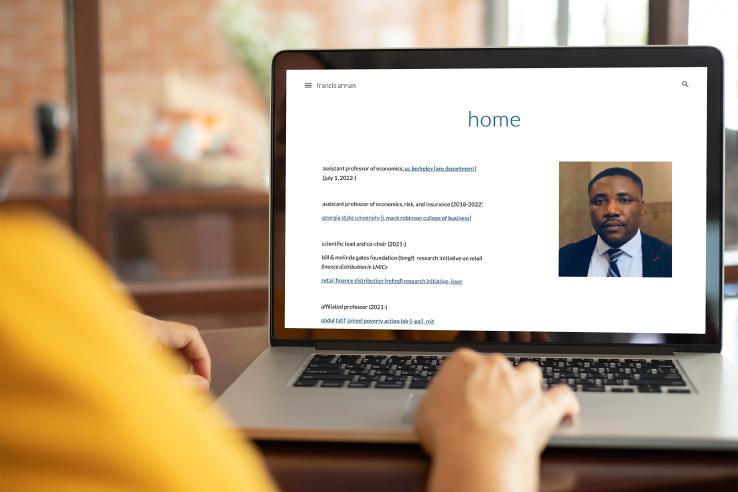

Building an academic website

A department biography page on a university website can be sparse on details, difficult to maintain, and can quickly become outdated—if this service is even offered by your university.

A personal academic website that you create and maintain yourself, on the other hand, lets you share more about yourself, your research interests, and your active and completed projects. Personal sites are also easier to update regularly and stay with you across job transitions if moving between institutions.

Many researchers use Google sites, which is free and easy to use. Other free options include Wordpress and Weebly.

Free options will have the name of the service in the url—e.g., a Google site might have the url “sites.google.com/site/janesmith.” It is completely normal and accepted for researchers to have websites with the host name in the url, as long as the url includes something intuitive and professional (like your first and last name). A simple and professional url can help to raise your online presence by ensuring accurate search results on search engines like Google. If you’d like a custom domain name (e.g., jane-smith.com), you can register one for a fee with sites like domains.google.com, godaddy.com or register.com.

Personal academic sites are usually as follows:

- Homepage: The contents should include:

- Your name and contact information (university email and address). Make sure your contact details are correct and that you monitor the email address listed

- A professional looking headshot

- A brief bio including your academic affiliation and position as well as a short research statement or featured work

- Links to your university page, Google Scholar page (more below), or other websites you use in a professional capacity

- Research: Include separate sections for published papers, books/book chapters, working papers, and works in progress. Within each section, papers can be ordered reverse chronologically (most recent at the top) or reverse chronologically by topic area. You can also add brief blurbs or abstracts for papers if you’d like, as well as adding links to published or working papers. (When linking to published papers, be sure to use the stable DOI link.)

- CV: your CV can be added as a PDF or you can embed a link to a Dropbox or Google Drive file of a PDFed CV. It’s important to keep this version of your CV updated - it’s where the general public is most likely to find you. See more below.

- Other optional sections:

- Research statement/about: A description of your research interests

- Fieldwork: List and description of active and past projects

- Teaching: If applicable

- Data and code: If you have any publicly available, e.g., on Github or elsewhere. These materials can also be embedded when listing your projects.

The design of your website should be simple, professional, and easy to read. Don’t use a patterned background, bright/unusual colors, or fonts you would feel uncomfortable using in formal writing. Use dark text on a light background, which is much easier to read than the reverse. Remember to proofread your content. See more tips from Elsevier.

A few examples running the gamut in terms of complexity are below. For each site, note the overall layout of each page, the tabs used (CV, research, etc.), the content of each tab, and the domain name.

Writing (and maintaining) a CV

Your CV may be the first thing people visiting your website look at. It should provide a concise, comprehensive, and well-organized view into your background and work.

Beyond posting it publicly on your website, you’ll likely have to include a CV when applying for grants, fellowships, or other positions. Keeping yours updated means you can send it off quickly without having to make major updates.

To do this, it’s best to have a master version of your CV that lists everything you’ve done and shorter, tailored versions for specific positions or grant proposals. Only share a PDF version so that others can’t easily edit it. Using a Latex template can save you a lot of time in formatting the CV properly; see some examples linked below.

Academic CVs are longer than a resume and should include everything relevant to the position, grant, or other activity for which you are applying—there is no page limit. Visually, they should look professional and clean and be easy to read. Keep the text in black and in a standard, professional font, and don’t include photos.

The sections listed below are typical of academic CVs; include whichever sections are relevant and in whatever order you prefer. Typically, items within sections are ordered reverse chronologically, i.e., the most recent item goes first. Common sections are:

- Name and contact information (always at the top). At a minimum, include a link to your website and your email address. You can also include your work mailing address and phone number.

- Education: Degrees, universities, dates

- Publications: Include the full citation, with the journal information, and a DOI if available.

- Working papers: Include the titles and co-authors and a link to the paper if available.

- Works in progress: Include the titles and co-authors. This can be combined with the above or kept as a separate section if you have a number of early-stage papers that are far from a finished draft.

- Grants: List the project title/topic, the funder, your role, any co-investigators, the amount, and the dates of the award.

- Presentations: If you have a very long list, you don’t need to include details here. For example, you could write: 2019: NEUDC, PacDev, ASSA, Michigan, Berkeley, Stanford, MIT. Some people split presentations further (e.g., invited seminars vs conferences) depending on what they want to emphasize.

- Teaching: List the course, the school, and the dates. Some people list teaching evaluations (e.g., 4.5/5) for each course. Graduate students can also list teaching assistant (TA) experience, just be sure to indicate for which courses you were the instructor vs. the TA.

- Awards/fellowships: List name of the award/fellowship, awarding institution (if not evident in the name of the award), and dates (years only).

- Referee service: List the journals for which you’ve served as a referee (no dates or frequencies needed). This list is usually alphabetical.

- Service: e.g., Service at your university or professional association, such as serving on a committee

A couple of example CVs and advice for CV writing include:

- Sample CVs from MIT and Harvard.

- See also the CVs of J-PAL affiliates, including Meredith Fowlie, Arya Gaduh, Koichiro Ito, and Yusuf Neggers

- CV writing advice from MIT, Cornell, and Elsevier

Latex templates:

- Overleaf and the site Latex Templates have a number of options. Some good ones include:

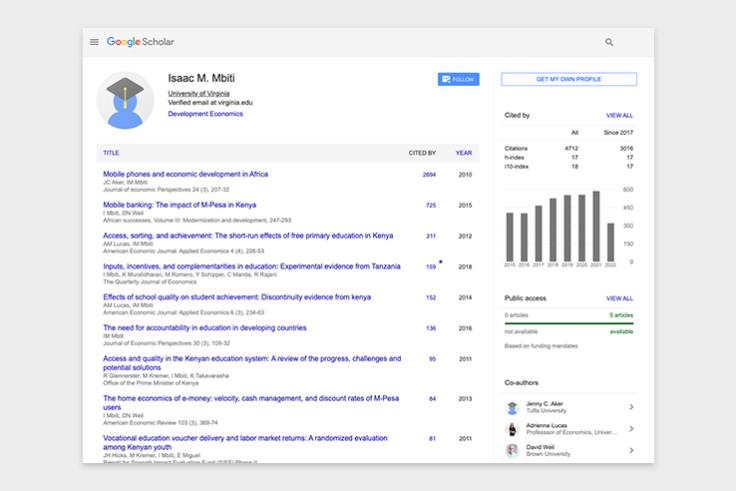

Creating a Google Scholar profile

Google Scholar pulls in and lists your publications and citations in one place, and is a low-cost way to increase your visibility. It should complement, not replace, a personal academic website, as it only lists publications.

You can set up your Google Scholar profile so that updates are done automatically or only with your review. Whichever route you choose, it is useful to periodically review your Scholar profile, as Google sometimes misattributes papers or categorizes publications that you may not want listed yet (e.g., very early drafts posted on conference websites). You can also sign up for alerts whenever one of your works is cited, which can be a useful way to see how your work is being referenced.

See Isaac Mbiti's and Tavneet Suri's pages for two examples, and this page on Google Scholar Profiles for more instructions on getting started.

Using social media

Twitter—specifically the hashtag #EconTwitter—has become a hub for economists to publicly share announcements including new papers, job openings for research associates (RAs), relocations, etc. The discussion is often lively and informative. It can feel uncomfortable to self-promote, but creating a Twitter profile, following other economists on Twitter, posting about your professional achievements (using the #econtwitter hashtag!), and engaging in discussions/responding to other economists’ posts are other low-cost ways to increase your visibility.

Sharing your research code and data (where appropriate)

Sharing de-identified data can increase the reach of your research. Doing so allows others to reuse your data to answer new questions, combine it with other data to draw out insights across studies (as in a meta-analysis or methods research), or to conduct replications of your analysis.

Beyond benefiting researchers and students who can learn from the data and code, original research data is a citable resource that can be linked to other study materials, including the paper and trial registration. This in turn can benefit you by raising your visibility and enhancing the credibility of your research. Note that data should only be shared if research participants cannot be re-identified and, if not solely owned by the research team, with permission from data owners (such as a data provider).

J-PAL offers free data publication services on any project funded by J-PAL. We also have two two step-by-step guides on 1) removing information that could be used to re-identify research subjects (a must-do before publishing research data), and 2) preparing data for publication, including suggested locations for storing data.

Takeaways

Building your online presence can help other researchers—and influential gatekeepers like conference planners and managers of professional networks—understand your research interests and seek you out for collaboration, and can greatly increase the accessibility of your research and publications. If you’re feeling overwhelmed and unsure of where to start, a good first step is to create a simple personal academic website, CV, and Google Scholar profile; the rest is still useful but less critical in enhancing your visibility as a researcher.

We hope these tips are useful! Explore J-PAL’s other resources for researchers.