Lesson #1 | What not-to-do: Wisdom from years of trials (and errors)

In January 2024, J-PAL South Asia organized its first ever public exhibition—Shaping Policy, Transforming Lives—to celebrate J-PAL’s 20 years of fighting poverty around the world using scientific evidence. The exhibition was a carefully curated selection of field stories by J-PAL South Asia staff from across India. Told through the written word, photographs, and artifacts, these stories embody two decades of the transformative impact of randomised evaluations in improving the lives of people.

Shaping Policy, Transforming Lives underscored the relevance of randomised evaluations to design poverty alleviation policies in India and elsewhere in the world. J-PAL South Asia—with its team of 230 research and policy specialists and large teams of field surveyors—has been working with its government and civil society partners across India for over a decade-and-a-half to implement rigorously tested policy interventions.

In this three-part series, J-PAL South Asia Executive Director Shobhini Mukerji reflects on the lessons learnt from these experiences as she builds her What-Not-Do-List to realise J-PAL’s goal of a poverty-free world.

Hi, I’m Shobhini, and I have graduated from The School of Trials (and Errors), or #YearsofRagra as I like to call it. My classroom has been government schools, villages and communities across India, and I have made my bed on chhats (terraces) and in paani-tankis (water tanks). My teachers have been the people and children with whom I’ve lived and worked over the last 25 years. When I have gotten stuck, I have found willing mentors in Rukmini Banerji and Esther Duflo—hopeful realists, humility and humour informing what they take on. I have gotten an earful when I needed it, encouragement to pursue my ideas, and sound advice on life, love, and children too. In all this, I’ve earned my Existential PhD! I’m excited to bring to you my learnings from School, and I hope you share the same excitement while reading them.

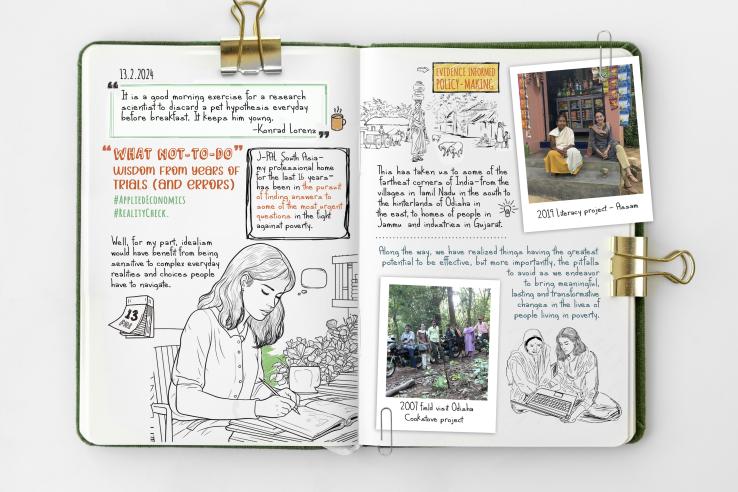

We often get asked: Who do you want to be stranded with on a deserted Island? Responses include what to do, how to do it. But what if someone tells you early on what not to do? Well, for my part, idealism would have benefit from being sensitive to complex, everyday realities and choices people have to navigate.

I call it my What Not-To-Do-List; what I have learnt from years of trials (and errors). #AppliedEconomics. #RealityCheck.

J-PAL South Asia—my professional home for the last sixteen years—has been in the pursuit of finding answers to some of the most urgent questions in the fight against poverty. This has taken us to some of the farthest corners of India, from the villages in Tamil Nadu in the south to the hinterlands of Odisha in the east, to homes of people in Jammu to industries in Gujarat. Along the way, we have realized approaches that have the greatest potential to be effective, but more importantly, the pitfalls to avoid as we endeavor to bring meaningful, lasting and transformative changes in the lives of people living in poverty.

Chipping away at the barriers that impede the improvement of health and education outcomes, technology fixes to solve process failures that curtail last mile access to social protection programs, or taking a ground-up approach in the design of solutions - in this twenty-year pursuit of evidence-informed policymaking lie our biggest lessons.

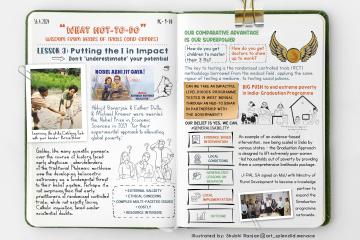

Lesson #1: Do not look for the silver bullet—there is none

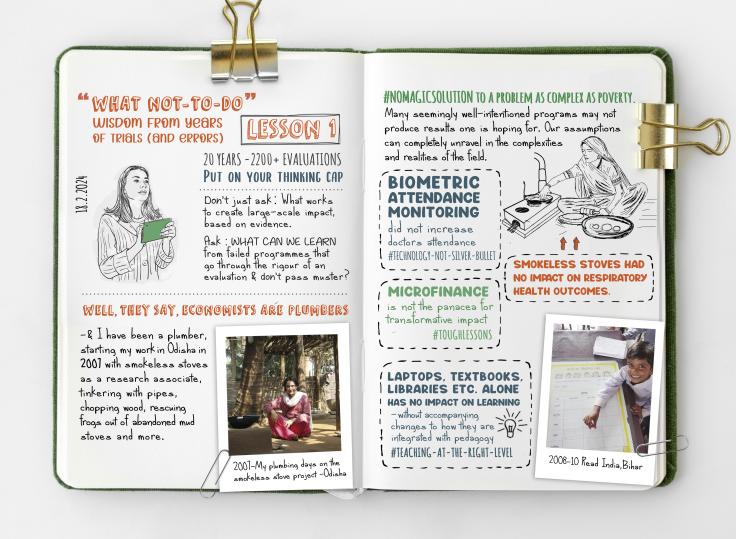

Well, they say, economists are plumbers—and I have been a plumber, starting my work in Odisha in 2007 with smokeless stoves as a research associate, tinkering with pipes, chopping wood, rescuing frogs out of abandoned mud stoves, and more. These stoves did not have the impact we had hoped they would. They did not reduce smoke exposure, improve health, or reduce fuel usage. I was 27 then, and still very much the bright-eyed field researcher, earnestly going house to house in the tribal forests of Ganjam and Gajapati districts, tracking which households rebuilt their stoves and repaired their chimneys.

We understood that people simply did not want these stoves. It seemed odd at first, but things started to become clearer as we spoke to the families.

Smokeless stoves demanded more time and effort than traditional stoves (chulhas in Hindi). People had to chop the wood into much smaller pieces to be able to use it in the smokeless stoves. The small openings in those stoves meant cooking time doubled. Besides, the mosquitos that had been unwittingly fumigated through the smoke from the traditional stoves were back in the house (giving them bednets for free perhaps might have helped).

Around the same time, our researchers in Karnataka were engaged in another plumbing fix with the Department of Health: testing the impact of an integrated medical information and disease surveillance system (or biometric attendance devices) on the attendance of doctors and nurses in primary healthcare centers.

Their results were equally puzzling. Despite the monitoring devices, overall attendance of doctors did not increase. We subsequently learnt that the government was unable to enforce the planned incentives and penalties, and as a result, very few doctors were disciplined.

There were larger issues at play here: the department’s reluctance to enforce penalties came from the fear of losing their doctors to the private sector. Private clinics offer more attractive work schedules and leave benefits, while doctors in the public health system earn less and are expected to work longer hours in far-flung corners of the country, where more than half of the population still lives. These results contributed to the government’s decision to cancel the planned scale-up of the program, saving millions of dollars in costs and countless hours of staff time.

The 27-year-old starry-eyed researcher was slowly beginning to understand the fundamentals of behavioral choices, incentives, and the larger political economy that govern why some interventions fail and some succeed.

For instance, take the early evidence from randomized evaluations in low- and middle-income countries that showed that the classic microcredit model did not lead to transformative impacts on income or consumption for the average borrower, nor did it turn them into entrepreneurs, thus debunking the silver bullet it was heralded to be.

AND HERE LIES PERHAPS OUR MOST IMPORTANT LESSON: There is no magic solution to a problem as complex as poverty. Many seemingly sensible and well-intentioned programs may not produce the results one is hoping for. That’s because despite having a great programme in theory, our assumptions can completely unravel in the complexities and realities of the field.

Over the last two decades, researchers affiliated with J-PAL have done over 2,200 evaluations to test policy interventions. A large number of them haven’t yielded impact. Together, we have learnt that technology solutions are not the silver bullet they are expected to be, that doubling teachers and giving free uniforms, or simply adding more education inputs such as laptops, libraries and textbooks alone, without any accompanying change in how they are integrated with pedagogy, has no impact on learning.

These kinds of findings turned conventional wisdom on its head, and made us, our researchers, and our partners put on our thinking caps. We had been asking ourselves what can work to create large-scale impact.

As we saw things play out in the field, we had to ask ourselves the hard question: what can we learn from the programmes that go through the rigor of an evaluation but don’t pass muster? Scaling down, changing the design, or deciding to not scale up an ineffective intervention can free up valuable time and resources and create the opportunity to try something new.

To be able to do this, it is vital to have partners who enjoy learning, unlearning and innovating. This, as you may have guessed, requires serious commitment of time, effort, and resources. But the payoffs are huge.

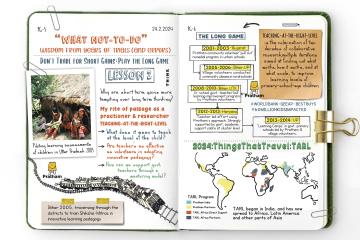

Herein lies my Lesson #2: Don’t trade for short gains—play the long game. That’s for the next blog. Stay tuned. In the meantime, begin compiling your list of who not to be stranded with on a deserted island for when you may need it…