Incentivizing public sector employees: The role of digital technology in enhancing the carrot and the stick

Employee effectiveness is a key driver of productivity and economic development in the public sector. But how does one motivate public sector employees to perform and deliver services? Understanding what drives these employees to work hard, and how different (dis)incentives can energize (or reduce) effort, is key. With this in mind, how can public sector institutions leverage digitization to monitor, motivate, and retain the best employees?

Positive and negative incentives: The carrot and the stick

Incentives are tools used to motivate employees to act in ways that align with the interests of the organization. Incentives are often thought of as economic goods, such as money, that are used to shift behavior. Pay for performance, where individuals receive additional payment for work completed, has been studied across a wide range of organizations, from schools to tax collection and procurement agencies. Studies have shown these schemes can be effective in improving civil servants' performance (for example, leading tax collectors to collect significantly more revenues), though are not a panacea for improving efficiency and may have some unintended consequences.

Yet providing monetary incentives can be expensive and/or politically difficult to implement. These barriers may lead one to look at non-financial incentives, such as favorable job postings based on prior performance, or an extrinsic reward such as gold stars based on performance. In addition, organizations might also consider negative incentives such as “punishment goods,” including reductions in payment, delayed promotions, or demotions.

There are many dimensions that influence the effort put in by employees. Innate characteristics, such as intrinsic motivation, may influence the success of certain incentive tools. Some tasks individuals would happily do voluntarily, without the need for an incentive. In addition, non-financial incentives may complement intrinsic motivations. In Zambia, the impacts of non-financial incentives were stronger for the most intrinsically motivated public sector workers. Thus, understanding which incentive works best in a specific environment and with a specific group of people is essential when designing effective programs.

Digitization to shift or enhance incentives

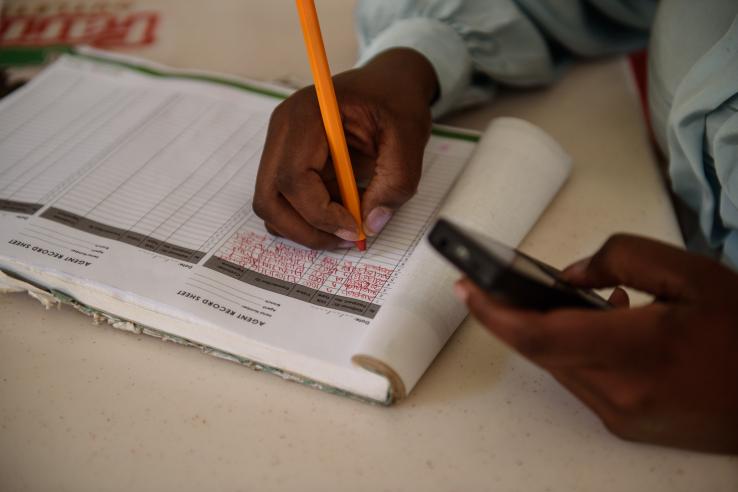

Various incentive approaches have differing merits or drawbacks based on the context in which they are implemented. Overall, digitization could help public sector institutions make better decisions by collecting better monitoring data and improving the delivery of incentives. Monitoring is central to implementing incentives, as these data are used to understand the level of performance and to allocate the associated reward (negative or positive) accordingly. Digital tools have the power to simplify data collection and make these systems more effective and efficient.

Digitization has the potential to enhance the way public sector employees’ performance is monitored. Digital systems using biometrics can be used to uniquely identify and accurately authenticate an employee at the workplace. These data can be verified by the employer remotely, who can make real-time decisions accordingly. Other digital tools, such as GPS and phone-based tracking, could also be used to monitor the performance of public sector employees.

Digitization has the potential to enhance the way public sector employees’ performance is monitored. Digital systems using biometrics can be used to uniquely identify and accurately authenticate an employee at the workplace. These data can be verified by the employer remotely, who can make real-time decisions accordingly. Other digital tools, such as GPS and phone-based tracking, could also be used to monitor the performance of public sector employees.

Biometric monitoring

Several studies examine biometric monitoring systems of public sector employees. In India, researchers looked at biometric tracking of healthcare workers and patients. Health workers and patients identified themselves with biometric finger scanners, linked to a computer system, when they came to a health center. Biometric tracking increased the likelihood that patients adhered to recommended tuberculosis treatment, improved healthcare worker attendance, and reduced misreporting of patient data by health workers. The biometric data collected made the healthcare workers more efficient, as it digitized their data systems and improved the ease of operations.

Another study in India tested whether a monitoring system that recorded employees’ fingerprints at the beginning and end of each day could improve staff attendance and patient health in primary health centers in Karnataka. The monitoring system increased attendance among medical staff, such as nurses and lab technicians, but not higher-tier medical staff such as doctors. However, absence penalties were not widely enforced. Implementation issues and the willingness to apply the attendance sanctions were key challenges—the combination of complex administrative processes for deducting leave plus difficulty in recruiting doctors to work for public sector salaries in rural health centers hindered penalty enforcement by administrative staff. The imperfect enforcement illustrates the limits of technological monitoring solutions when they are not combined with changes in the broader rules governing health workers.

GPS and phone-based monitoring

Researchers partnered with the Government of Paraguay to measure the impact of a new monitoring technology—GPS-enabled cell phones—on the job performance of agricultural extension agents. Overall, cell phones improved agricultural extension agents’ performance by increasing the share of farmers visited, and researchers found that supervisors possessed useful information regarding which agricultural extension agents’ performance would improve the most from phone-based monitoring.

In Telangana, India, researchers conducted a study to test the impact of a cell phone-based monitoring system on the delivery of government-issued payments for farmers. The phone-based monitoring scheme significantly improved the likelihood of farmers ever receiving their payments as well as receiving them on time, indicating improved performance by on-the-ground service providers in delivering payments to farmers.

Digitization has the potential to transform the way monetary incentives are delivered. The growth in digital technology, especially mobile money, allows governments to extend incentives and payments to employees who previously may have been inaccessible. For public sector workers who live in remote areas, the ability to receive money directly through mobile money wallets, rather than going to town to collect their payments, could decrease the time lost due to travel and waiting in queues. Digital identifications (IDs) allow for work to be tracked in a more precise way, for the allocation of incentives to be more accurately measured, and for benefits to be disbursed in a more predictable manner.

Ongoing work in Afghanistan examines the impacts of the modality of payments to public sector workers. In partnership with the Ministry of Education, researchers are conducting a randomized evaluation to study whether mobile salary payments, compared with the status quo of cash payments, improve learning by increasing teacher attendance and morale.

While digitization can have substantial cost implications, it can be cost-effective. Digital technology can be used to monitor performance and improve the delivery of incentives, but a central question remains on the cost-effectiveness of these investments.

In the study of biometric monitoring of health workers in India, the implementation and enforcement challenges meant that the technology was not effective in its intended role. The choice not to scale the program saved taxpayers an estimated US$604,000 in the initial equipment costs alone of providing all the Primary Health Centers with the devices. However, there are cases where the implementation of technologies has been cost-effective. For example, the India cellphone-based monitoring of a government payment program was highly cost-effective, costing 3.6 cents for each additional dollar delivered. These results suggest that phone-based monitoring can be implemented by governments at a large scale and deliver significant improvements in service delivery across millions of beneficiaries in a quick and cost-effective manner.

Open questions

Managing incentives is central to the delivery of services. What design features and incentive structures can be built into public sector wage payments to boost the productivity of front-line public servants? Can the expanding formal economy be an avenue to increase the tax base through incentives and simplified processes introduced by payments and digital IDs? These are all questions that fall within the Digital Identification and Finance’s (DigiFI) research agenda. For more information, please see our framing paper.

Author’s note: This is the sixth blog in the DigiFI series on the various aspects of their research and policy priorities. The next blog will explore to what extent digitization can improve take-up.