Summer Jobs Improve Employment Outcomes for Connected Youth

- Urban population

- Youth

- Arrests and convictions

- Employment

- Enrollment and attendance

- Crime

- Apprenticeships and on-the-job training

- Coaching and mentoring

- Psychosocial support

In an effort to address youth unemployment and violent crime, policymakers have supported numerous summer jobs programs in the United States. Researchers studied the impact of a summer jobs program in Chicago on crime, education, and employment. The program dramatically reduced violent-crime arrests, including in the following school year, though it did not influence schooling or formal employment, and may have increased property crime in future years. Using a machine learning technique, the researchers find that the youth with the largest improvements in employment are not the disconnected youth usually targeted by employment programs.

Policy issue

Since 2012, the youth summer employment rate has hovered between 9.6% and 18%1 , while recent increases in violent crimes against youth are causing policy concern. One way policymakers have tried to address these issues is by providing youth with training and job opportunities. While only very intensive programs typically improve employment outcomes for youth, less intensive programs have successfully reduced violence. How these less intensive programs reduce violence is not well understood. Researchers look at the impact of a summer jobs program on subgroups to better understand whether improved future employment is the key driver of the violence decline or whether there are other mechanisms at play.

Context of the evaluation

This evaluation was implemented in partnership with Chicago’s Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS). DFSS designed and implemented a summer jobs program, One Summer Chicago Plus, with local non-profit agencies during the summers of 2012 and 2013.

The program served primarily Black youth from low-income neighborhoods. While the 2012 cohort included male and female students aged 14-21 from 13 Chicago public high schools, the 2013 cohort was entirely male, older, more likely to have prior involvement in criminal activity, and more likely to have lower attendance in school.

Details of the intervention

The One Summer Chicago Plus program offered youth a five hour per day, five day per week summer job at minimum wage for six to eight weeks. All youth were assigned a job mentor, and some youth spent two of the five daily hours in a social-emotional learning curriculum, based on cognitive behavioral therapy principles. The program cost about $3,000 per participant.

In 2012, 1,634 youth aged 14-21 applied to the program, recruited from Chicago public schools. These youth were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- Summer jobs only (25 hours per week)

- Summer jobs (15 hours per week) plus social-emotional learning curriculum (10 hours per week)

- Control group

In 2013, 5,216 young men aged 16-22 applied to the program, recruited from an applicant pool for broader summer programming in Chicago or referred from the criminal justice system. Youth were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- Summer jobs plus social-emotional learning curriculum (with invitations to additional structured activities throughout the following year) or a waitlist for this program

- Control group

The researchers measured crime, school enrollment, school attendance, course grades, and formal sector employment using data from DFSS and the Illinois State Police, Chicago Public Schools, and the Illinois Department of Employment, respectively.

Results and policy lessons

Main Takeaways: The summer jobs program substantially reduced violent-crime arrests both during and through one year after the program. The program did not reduce other types of crime arrests, and appears to have increased property crime arrests although results were imprecise. The program did not influence schooling or formal employment.

Only 75 percent of students assigned to the program in 2012 and 30 percent in 2013 ultimately participated, largely due to the program and waitlist design (the maximum possible participation rate in 2013 would have been 38 percent). The impacts reported below are estimates of participating in the summer jobs program and have been scaled to account for the fact that not everyone who was assigned to the program actually received summer jobs.

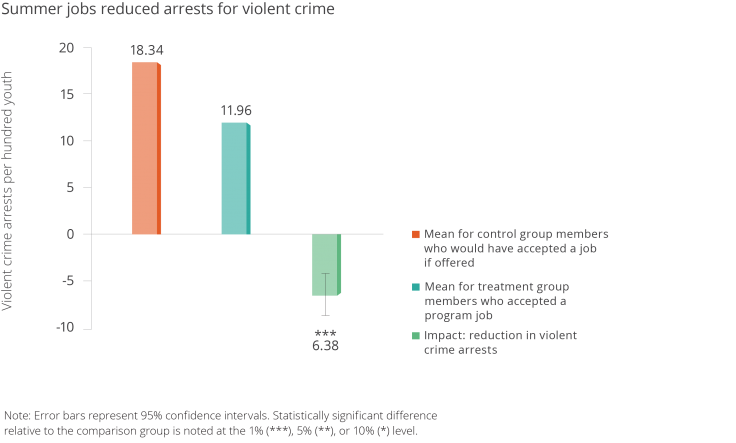

Violent Crime: The program resulted in 6.4 fewer violent crime arrests per 100 participants in the year following the start of the program, a 35 percent decline. The majority of this decline occurred after the program summer. The social benefits from the reduction in violence may be nearly 6 times larger than the program’s costs.

Property Crime: By contrast, the program appears to have increased property crime by 45 percent, causing 5.8 more property-crime arrests per 100 participants over the 2-3 years after the program began. Opposing effects for violence and property crime are consistent with previous studies. One explanation is increased opportunity for theft but decreased interaction with fight-prone peers.

Education: The program had no significant impact on school enrollment, attendance, or grades during the school years after the program.

Employment: The program did not improve overall employment outcomes, though participants were more likely to work future jobs with their summer employers, perhaps due to strong relationships. Using a machine learning technique, researchers identified a group that did show improved formal sector employment following the program. This group was somewhat younger, more Hispanic, more female, less criminally-involved, and more engaged in school than the overall study population.

Mechanisms: Both the group of participants who were more likely to work in the formal sector and the group who were not experienced significant declines in violence. Some people hypothesize that the success of summer jobs programs in violence reduction may come from improving job prospects or simply filling up youth’s free time over the summer. Since both groups who did and did not benefit on formal employment after the program experienced drops in violent crime, and since the reduction in violence persisted after the program summer, these explanations are unlikely. One potential explanation is that the program helped youth learn to better avoid or manage conflict.