Preventing violence at scale: How practitioners are using evidence to adapt and scale CBT programs

In May, J-PAL convened a panel of experts at PeaceCon 2023 to discuss learnings from adapting and scaling four different CBT-inspired programs in the United States, Liberia, South Africa, and Mexico. Christopher Jaffe, Klubosumo Johnson Borh, Lauren Roode, and Helke Enkerlin Madero share their insights below.

A psychosocial strategy for crime and violence prevention

A growing number of crime and violence prevention programs are drawing on psychosocial techniques to help shift people’s behaviors and attitudes, offering a potentially low-cost alternative to more traditional security sector strategies. In particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been increasingly applied in diverse contexts to reduce antisocial and violent behavior and to help people exposed to violence process their experiences. CBT is a psychotherapeutic practice that shifts participants' thoughts and behaviors; it has most commonly been used to address mood and anxiety disorders, addiction, unhealthy communication patterns, and even unwanted habits like forgetting to take a medication.

Despite increasing evidence on the efficacy of CBT-based approaches in reducing criminal and violent behaviors, open questions remain as to whether and how these programs can replicate and scale successfully in new contexts—questions relevant to many peacebuilding and conflict prevention interventions.

CBT programs across diverse contexts

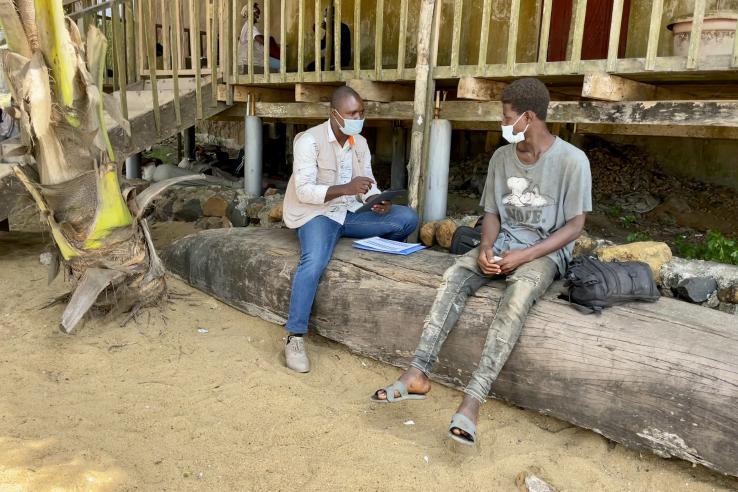

At the PeaceCon panel, four experts shared their experiences from helping shape the Becoming a Man (BAM) program in Chicago, the Sustainable Transformation of Youth in Liberia (STYL) program in Monrovia, Shukuma in the Western Cape of South Africa, and a pilot project with police in Mexico City.

The programs generally included interactive group and activity-based therapy sessions rooted in CBT principles. Sessions focused on behavior change techniques to help participants identify and change harmful thought patterns, regulate their emotions and behaviors, plan ahead and set goals, and address cognitive biases as a means for improving decision making.

As in many CBT-based interventions, the featured programs were relatively low-cost compared to traditional crime and violence prevention programs They used simple, standardized curricula usually delivered by informally trained facilitators and complemented by prerecorded video lessons in the case of Mexico City. These attributes could make replicating these approaches in new contexts more feasible.

|

Location |

Program |

Target Population |

Key Program Details and Findings |

|

Chicago, USA |

BAM1 |

7th-10th grade male students at risk of school dropout in high-crime neighborhoods |

- Weekly hour-long group therapy sessions during school hours for 1-2 school years, with the aim of improving long-term life outcomes for youth - Researchers found that participants were less likely to be arrested during the program, more likely to graduate, and more likely to make considered decisions.2 |

|

Monrovia, Liberia |

STYL |

Young men at the highest risk of engaging in crime and violence (25 years old on average) |

- Group therapy sessions lasting four hours each, held three times per week for eight weeks, and one-on-one counseling - Some participants received a US$200 unconditional cash transfer - Researchers found large and persistent impacts on participants’ criminal and violent behavior, which continued to be observed ten years after the program was originally implemented. Receiving therapy also improved some measures of self-control and mental health. |

|

Western Cape, South Africa |

Shukuma |

8th and 9th grade students |

- Series of 10-15 small-group CBT-inspired sessions during class; designed to address youth violence by helping students develop socioemotional skills - By the end of 2022, 46 schools had piloted the program, reaching around 2500 students |

|

Mexico City, Mexico |

CBT for Mexico City’s Police |

Police officers in Mexico City |

- Ongoing pilot program consisting of eight two-hour group sessions with video lessons and facilitated discussions. - Aims to address the higher prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among police. By improving how police officers manage their emotions and make decisions, the program may also help address police misconduct and excessive use of force against citizens. |

Our panelists bring expertise from across their organizations

Meet the Experts

- Christopher Jaffe has served on the leadership and program design teams for two CBT-inspired programs, the Becoming a Man (BAM) program for youth at risk of school dropout and crime in Chicago and the Shukuma program for students in the Western Cape.

- Klubosumo Johnson Borh is the founder and CEO of the Network for Empowerment and Progressive Initiatives (NEPI), which delivers the CBT-inspired STYL program to young men at the highest risk of engaging in crime and violence in Monrovia, Liberia.

- Lauren Roode, a Senior Policy Associate at J-PAL Africa, partnered with South Africa’s Western Cape Education Department from 2020 to pilot and adapt the Shukuma program to address student-on-student violence, leveraging evidence from other countries.

- Helke Enkerlin Madero is a Senior Policy Manager at Innovations for Poverty Action’s Mexico office. She led the implementation of a CBT-based pilot program for police officers in Mexico City.

Lessons on designing, adapting, and scaling CBT-inspired programs

The following insights were shared during the panel discussion.

How has research and evidence helped shape the design of the CBT programs you have worked on?

Johnson Borh on the STYL program in Liberia: Partnering with researchers on a long-term randomized evaluation showed us that we were doing something meaningful and ways we could improve. We learned from the evaluation that therapy alone was successful, but combining therapy with the cash transfer was the most effective version of the STYL program. Now, including a cash transfer is a standard part of the STYL model.

We also learned that STYL was more beneficial for some young people than others. Though we targeted youth with a high risk of engaging in crime and violence from the start, the evaluation showed there was a subset of the most at-risk youth that ultimately benefited much more from the program. From this, we realized we needed to target more narrowly when recruiting future beneficiaries. In our ongoing 2023 scale-up, we revised our recruitment strategy accordingly to be able to identify young people at the very highest risk of engaging in crime, starting from our community scoping phase to our intake survey.

Christopher Jaffe on the BAM program in Chicago: BAM was developed through the lived experience of the program founder, Anthony Ramirez Di Vittorio, coupled with clinical theories supported by evidence. A randomized evaluation helped to confirm what we suspected to be true rather than informing the program in advance; this evidence then helped solidify the decision to scale the program to new cities. We also used outside evidence, including from the University of Chicago’s Consortium on School Research, to contextualize the work of BAM.3 Scaling BAM also would not have been possible without research partnerships, particularly with the National Implementation Research Network. Their evidence-based approach to implementation science helped BAM scale while maintaining fidelity to the evaluated model.

Lauren Roode on the Shukuma program in South Africa: Shukuma was designed and adapted based on evidence from a variety of evaluated programs, including BAM and STYL. In 2019, J-PAL Africa was approached by the Western Cape Government’s Department of the Premier to identify a behavioral program that could reduce violence in schools.

We ultimately landed on piloting a CBT-based program based on our research of what types of programs may work best and our application of the generalizability framework, a process for determining if evidence in one context will translate and apply to another.

We compared the local conditions in the Western Cape to the conditions where other evaluations of CBT-based programs took place, considered the lessons on behavior available from existing evaluations, and factored in local implementation capacity. For example, during the BAM evaluation, the local conditions were such that high levels of crime and violence were prevalent among youth, youth responded impulsively to high-risk situations, and youth had limited access to psychosocial support and mentoring in schools, similar to in the Western Cape.

On local implementation, we spoke with researchers who previously implemented similar programs to identify what challenges they faced, the implications for program design, and how we could overcome these challenges in South Africa.

For example, in a CBT-inspired program for students in Mexico, researchers found that low student attendance was linked to stigma around participating in the program, a delayed program start date, and hosting sessions outside of regular school hours. This, combined with our own pre-pilot experiences, led us to update the Shukuma branding to seem fun and engaging to students and to encourage our partners to implement the Shukuma program in class.

Helke Enkerlin Madero on a CBT-based pilot in Mexico: Starting out, our original goal was to find a way to improve citizen trust in the police. It was by reviewing and adapting existing evidence that we decided to pursue a CBT-based model for police officers. Based on our other research in Mexico, we found that one possible way of building trust was through positive one-on-one interactions between citizens and police.

We then started researching interventions that could improve how police react in one-on-one settings and found that CBT was effective at improving decision making in other populations. We also drew on research with first responders and populations living with PTSD from exposure to conflict. This combination of evidence informed the structure of our program. However, we also want to advance the field by directly researching the link between citizen trust and CBT for police officers.

What practical lessons have you learned from adapting and implementing CBT programs in new contexts, including on how to draw out generalizable lessons from research when bringing an intervention to a new environment?

Christopher Jaffe: My process for cultural adaptation begins with a general framework applicable to a range of group-based CBT-inspired interventions. The specific framing and language with which you present the intervention takes the most care during the adaptation process.

Successful adaptation requires a significant amount of in-person and virtual research before drafting a modified intervention, including through focus groups or individual interviews with NGOs serving the target population. Then, once I have drafted a concept for a new program, I work with local social work consultants to further develop the most appropriate intervention.

Most importantly, it’s essential to work in partnership with and have a feedback loop with members of the local community so the program can be tailored to their needs. This could include hosting group test sessions where participants’ and facilitators’ feedback is incorporated into the final program design.

Johnson Borh: While NEPI is still preparing for many of our scaling plans, we have already learned a lot while trying to determine the appropriate path-to-scale model or “vehicle” for scale. Our program could be scaled through partnerships with the government, local NGOs, or international organizations, or we could increase capacity within our own organization to deliver the intervention to more people.

However, the exact implementation model would likely differ under each approach and it isn’t immediately clear which vehicle would be best suited to reach our target population of the most at-risk youth, which traditionally are difficult to reach. For example, we had to ask ourselves if partnering with the government would make sense: do they have the capacity to deliver the intervention as designed or is there scope for us to co-create an adapted form of the program? Ultimately, we plan to partner with a range of NGOs, including grassroots organizations, to work with governments in delivering the program at scale. We will streamline the model to make it easier for other organizations to replicate and monitor for effectiveness and model fidelity.

Potential partners have also asked us to consider adapting the STYL program to women. Before deciding whether to pursue this or not, we needed to first think critically about how such a program would be adapted to address the unique needs and risky behaviors of vulnerable women in Liberia, which are largely different from the criminal and violent behaviors the STYL program was originally designed to address in men.

While we often talk about adapting a program from one country to another, it is also important to not assume that because a program worked with one population in a given context, it will also work with another population in the same setting.

Where do you think there are open implementation and path-to-scale questions for adapting CBT-based approaches and other similar interventions to new contexts?

Lauren Roode: I think the open questions for Shukuma can be divided into three categories: scale-, spillover-, or adaptation-related. There are open questions on how to sustain the program at scale in schools—for example, could teachers be trained to successfully facilitate in-class CBT sessions or are external facilitators a feasible option at scale?

On spillovers, we found that the Shukuma facilitators themselves, as young job seekers, also reported changes in their own behaviors after leading the CBT sessions. In the future, we would like to explore how implementing CBT programs can impact facilitators’ own socioemotional skills, labor market outcomes, and potential spillovers to the broader community.

Finally, on adaptation, we noticed in Shukuma that some students struggled to understand some modules, likely due to challenges with translating words or concepts into the local language that are not culturally relevant. Additional research could help make the program more accessible.

Helke Enkerlin Madero: Many open questions for our work with the Mexico City police are around relevance and scope. On relevance, we considered whether other interventions designed for populations that aren’t regularly exposed to life-threatening situations are relevant enough to police officers or if we should look for something more tailored.

On scope, the Mexico City police includes about 77,000 officers, making it only feasible to deliver CBT sessions in group settings. A concern we are dealing with is the risk that we may expose officers to topics that may be triggering to them during the group sessions without having the capacity to respond to their needs with individualized counseling.

Further, there is a concern that the police department may not be able to sustain the program over the long term. While we don’t envision officers going through the two-month program repeatedly, ideally they should be able to receive some form of reinforcement, mentoring, or other follow-up services to maintain the potential positive effects from the program.

Christopher Jaffe: One important open question around implementation is how to balance the clinical complexity of a CBT-based program with the education level of facilitators. Implementers need to think about what outcomes they hope to achieve and what they can afford for facilitation. In a best case scenario, clinicians could implement most programs, but they can often be prohibitively expensive.

Some programs are also designed to be more clinically complex than others. For example, in BAM, most facilitators had a master’s degree in social work, counseling, or psychology, which we felt was necessary for the level of clinical oversight designed into the program. In Shukuma, while the program was originally designed to be implemented by clinicians, the funding model changed and required us to train young high school graduates without a clinical background as facilitators.

This required us to adapt the overall complexity of the program and to prepare facilitators for potentially sensitive conversations with participants. In general, it is important that a program is designed with the facilitators’ level of expertise in mind.

Addressing practical challenges

Adapting and scaling CBT-based programs can present implementers with many practical challenges, ranging from how to determine the optimal implementation conditions to understanding if the underlying mechanisms behind impact in one setting exist in another. To help address these challenges, the panel of expert practitioners highlighted the following considerations based on their hands-on experience with four different CBT-inspired programs in distinct settings:

- Evidence can help practitioners inform and adapt their program design to increase effectiveness (e.g. adding a cash transfer to the final STYL model). However, when deciding to adapt or scale a program to a new context, practitioners must consider if existing evidence is relevant and generalizable to the new setting, target population, and outcomes they have in mind. Long-term research partnerships and implementation science can help maintain fidelity to an intended program design.

- Cultural adaptation is key to successfully adapting or scaling a model from one context to another. This helps ensure a program will be relevant and accessible in a new context, or even with a new population in the same location (e.g. adapting a program designed for at-risk men to be relevant for women).

- Scaling and adaptation plans must also address practical barriers to successfully implementing a program in a new setting, including ensuring there is sufficient administrative capacity to deliver a program as designed. This would also include factoring in the feasibility of complementary services (e.g. one-on-one counseling to interested participants after a program ends) that may help sustain program impacts. Practitioners should consider multiple possible path-to-scale models and think about how their programming and necessary partnerships would change under each option.

- Implementers should carefully consider the level of training, formal education, and clinical expertise that should be required of facilitators of CBT-inspired programs. At minimum, facilitators must be prepared to adequately respond to the complex emotions and experiences participants may share with them to ensure the program does no harm. However, requiring facilitators to be highly trained clinicians may not be necessary for a program to be effective, and may not be feasible at scale, especially in resource-constrained contexts.

[1] The details in the table describe BAM as implemented when the program was evaluated in 2009–2010 and 2013–2015. BAM now includes 7th-12th graders and runs for two school years.

[2] Heller, Sara B, Anuj K. Shah, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig, Sendhil Mullainathan, Harold A. Pollack. 2017. “Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chicago”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1):1–54, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw033

[3] The report synthesizes knowledge across disciplines on what young people need to learn to grow up successfully and how programs like BAM could support that process.

Related Content

Shukuma in South African schools: Adapting evidence on cognitive behavioural therapy-inspired programmes to reduce violence

Tackling crime and violence in Latin America with cognitive behavioral therapy