Discrimination in Hiring and Anonymous CVs in France (CV Anonymes)

- Job seekers

- Large enterprises

- Multi-national companies (MNCs)

- Discrimination

- Employment

- Recruitment and hiring

- Regulation enforcement programs

Race and class discrimination can relegate minority groups to unemployment or low quality jobs, sometimes despite their qualifications. In collaboration with the French employment agency Pôle Emploi, researchers evaluated whether interview and hiring rates of minority candidates changed when employers collect anonymous resumes. Making resumes anonymous did not affect the average number of interviews and job offers volunteer firms made, the length of the hiring process, or the use of other recruitment channels, but it reduced the likelihood that firms interview and hire minority candidates.

Policy issue

Race and class discrimination continue to be pervasive in countries throughout the world, and can relegate minority groups to unemployment or low quality jobs, sometimes despite their qualifications. Employers can gather information about the race or class of job applicants in several ways, most obviously if their name or address signals that they come from a certain ethnic background or neighborhood. Previous studies in the United States and Canada, which sent out resumes with different genders and ethnic backgrounds, showed that minority applicants consistently receive fewer interview offers. One way to prevent this sort of discrimination could be to institute blind hiring procedures, where employers cannot see applicants’ name or address. However, there have been few evaluations of how these policies actually affect employment opportunities for marginalized groups.

Context of the evaluation

France has a large population of immigrants from West and North Africa, many of whom live in poor neighborhoods. In general, minority populations have higher levels of unemployment than the rest of the population: in 2009, the unemployment rate among non-immigrants in France was 8 percent, while it was 15 percent among immigrants. There are many potential reasons for this stark difference—lower educational levels, lack of social networks that link minority jobseekers to information about job vacancies, and employment discrimination. If employers wish to avoid hiring candidates from lower socio-economic groups or minorities, then resumes containing candidate names and addresses may offer a way for them to identify such applicants. In an attempt to combat this discrimination, France passed a law in 2006 that mandated the removal of candidate names and addresses from all application materials submitted for jobs, making them anonymous. However the law was never enforced. Instead, in 2009 the government decided to launch a program where firms could choose to accept only anonymous resumes during hiring processes managed through the public employment service, Pôle Emploi.

Details of the intervention

In collaboration with the French employment agency Pôle Emploi, researchers evaluated whether interview and hiring rates of minority candidates changed when employers collect anonymous resumes. Firms posting job offers at Pôle Emploi had the option to ask for an agent to make a first screening of applicants based on their resume for free, instead of receiving applications directly from jobseekers. All firms with more than fifty employees that requested this service, and that posted a position lasting longer than three months, were invited to participate in the study. Firms were free to enter or decline.

Among all the firms that were offered the possibility to participate in the program, 62 percent accepted (1,005 participating firms in total). For participating firms, a Pôle Emploi agent selected an initial pool of applicants that matched the skill set for the posted job. Then, job postings and their corresponding pool of resumes were together randomly assigned to one of two groups: an anonymous recruitment procedure or to a comparison group.

In the anonymous recruitment procedure, all resumes sent from the employment agency were made anonymous by removing the applicant’s name, address, gender, nationality, ID picture, age, marital status, and number of children. In the comparison group, resumes coming from the employment agency included this information. It is important to note that in both the intervention and comparison groups, employers also received applications from other sources in addition to Pôle Emploi. Researchers collected information through administrative data and phone surveys on the participating and non-participating firms, their applicants, and the interview and hiring outcomes of 1,268 applicants that had been randomly assigned to the intervention and comparison group.

Results and policy lessons

Making resumes anonymous did not affect the average number of interviews and job offers volunteer firms made, the length of the hiring process, or the use of other recruitment channels, but it reduced the likelihood that firms interview and hire minority candidates.

Removing personal information from resumes did not affect the number of interviews and job offers participating firms made. Making resumes anonymous did not affect the average number of interviews and offers for employment made per job posting, the length of the hiring process, or the use of other recruitment channels.

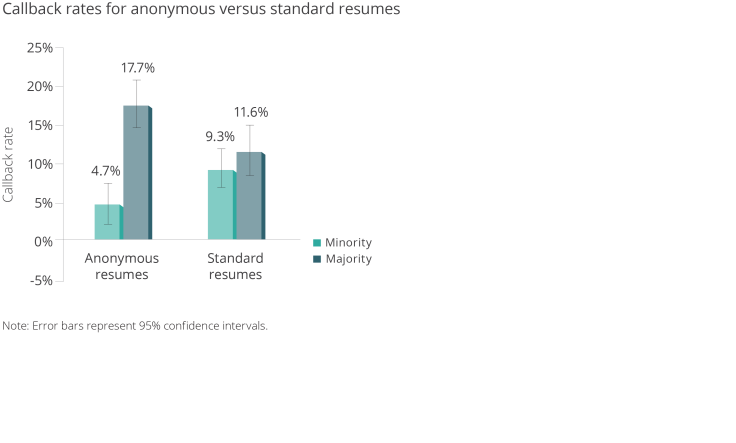

However, when resumes were made anonymous, participating firms were less likely to interview and hire minority candidates. Anonymizing resumes widened the interview gap between non-minority and minority candidates by 10.7 percentage points, from 2.4 percentage points in the standard procedure to 13 percentage points in the anonymized procedure. At the hiring stage, the recruitment gap widened by 3.7 percentage points.

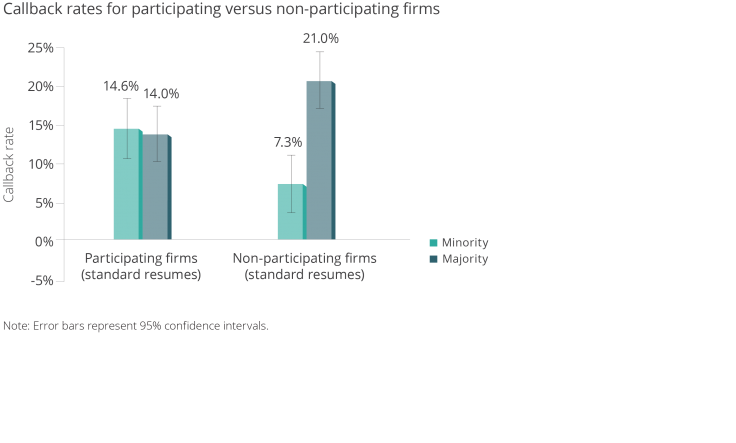

Although participating and non-participating firms were similar in most observable characteristics, researchers found that the firms that volunteered to participate in the study were more likely, on average, to interview and hire minority candidates when using standard, name-bearing resumes than those who declined. They also found that participating firms attached less importance to interrupted work histories or other negative signals for minority candidates. This suggests that anonymizing resumes may have made it more difficult for employers that were originally more favorable to minority candidates, to identify these candidates, and to assess their application in light of the adverse employment conditions many of them face.

The results of the evaluation generated considerable discussion in France amid a contentious broader debate about the best policy options for reducing discrimination in hiring and, in 2015, the government decided to abandon the policy. For more details, see the evidence to policy case study.