Reducing the Incidence of Vote Buying in Uganda

- Voters

- Electoral participation

- Transparency and accountability

- Elected Official Performance

- Voter Behavior

- Corruption and Leakages

- Community participation

- Information

Democracy in many developing countries is undermined by the widespread provision of cash or goods for votes (i.e., vote buying). During the 2016 Ugandan elections, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation of an anti-vote-buying campaign to study voter behavior and electoral outcomes. Overall, the campaign did not reduce the extent of vote buying, but it had substantial effects on electoral outcomes. While people continued to accept gifts from all candidates, votes swung from well-funded incumbents-who engaged in the bulk of vote buying before the campaign-towards their poorly-financed challengers in areas exposed to the campaign.

Policy issue

Vote buying practices are common in many developing countries: Politicians provide money and goods to voters, drive likely supporters to the polls, and target gifts to voters who are likely to reciprocate with their vote. These practices undermine democratic elections because individuals who sell their votes are unlikely to be able to demand public services from the candidates to whom they sold their votes.

To reduce vote buying, governments and civil society organizations have conducted information campaigns about candidate qualifications and encouraged voters to either refuse payments or accept them and vote for their preferred candidate anyway. While smaller-scale information campaigns have been effective at convincing some voters to refuse to sell their vote, it is unclear whether such interventions reduce overall vote buying or simply displace vote buying to other areas.1 2 3

Context of the evaluation

Despite competitive national elections every five years, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) and its leader, President Yoweri Museveni, have been in power in Uganda since 1986. While local elections are viewed as fairly competitive, vote buying and voter intimidation is fairly common in national elections, and most votes are bought by incumbents. Politicians and political parties bring voters to the polls through a combination of money, gifts, and transport.

In February 2016, Uganda held general elections, including voting for President and Members of Parliament. Ugandan and international observers provided mixed opinions about the fairness and transparency of the election.4

Details of the intervention

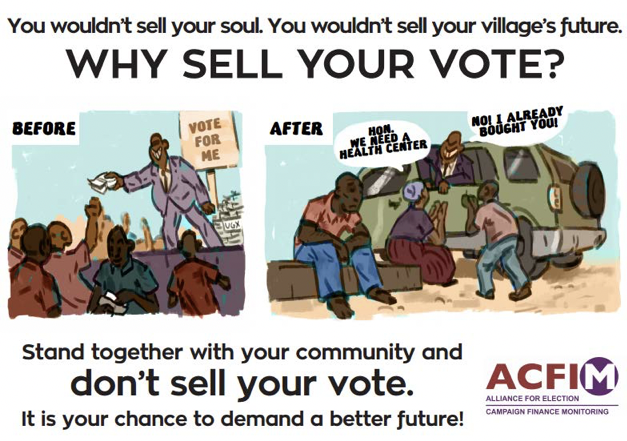

Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation of a large anti-vote buying campaign implemented by the Alliance for Election Campaign Finance Monitoring (ACFIM) in partnership with the National Democratic Institute (NDI). The campaign focused on dissuading citizens from selling their votes, and the evaluation measured turnout, vote, perceptions of vote-buying, and changes in candidate behavior.

Researchers conducted surveys in approximately 2,796 villages (as well as 1,399 additional villages outside the sample of this particular study) across 53 districts during the February 2016 Ugandan general elections. These villages were spread across 918 “parishes” (groups of 3 to 10 villages) typically targeted by vote buyers. Parishes were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- Voter Intervention: Prior to the election, activists used community meetings, posters, and robo-calls to try to persuade villages to commit to not selling their votes. As part of the intervention, villages made a collective declaration to refuse offers of gifts or money in exchange for votes, creating “no vote-buying villages.”

- Comparison Group: Villages in this group were not exposed to the intervention.

Researchers also randomized the share of villages receiving the intervention within each parish, allowing them to determine whether the effects of the campaign in one village spilled over into nearby villages that did not receive the intervention.

Results and policy lessons

While the campaign did not reduce the extent of vote buying, it had substantial effects on electoral outcomes. In areas exposed to the campaign, vote shares decreased for incumbents (who were well funded and engaged in the bulk of vote buying before the campaign) and rose for challenger candidates (who were less well-funded). Evidence suggests that people in the intervention group voted for their preferred party while still accepting gifts from all sides.

These findings suggest that informing voters about vote buying and its social costs can shift voter norms and behavior, influence the campaign strategies of political candidates, and ultimately change voting outcomes.

Vote buying: The campaign did not reduce the extent of vote buying: overall, the campaign did not have a significant impact over an index of vote buying constructed by the researchers before the research project began. Voters in campaign villages and surrounding villages even reported an increase in challenger candidates’ vote buying, measured in terms of cash and gifts received by voters.

Social Norms: The campaigns did, however, change social norms around vote buying. Post-election surveys suggest that voters continued to accept gifts from all candidates, but cast their votes independently of the gifts. Voters also became more aware of the negative consequences of vote-buying: the share of voters who believed that selling votes would negatively affect community services increased between 5 to 10 percent compared to non-campaign villages.

Electoral outcomes: Because voters no longer felt compelled to vote according to compensation, the campaign had a significant effect on electoral outcomes. Incumbent candidates’ vote shares diminished by between 0.063 and 0.185 standard deviations in campaign villages: an effect large enough to sway an election from an average incumbent to challenger candidate. The campaigns also led to higher voter turnout, due in part to challenger candidates that increased their campaigning and vote buying efforts in places previously dominated by well-funded incumbents.

Based on the results of this evaluation, NDI and ACFIM have piloted interventions combining the anti-vote-buying message with candidate pledges to not offer gifts in exchange for votes. These interventions also included a hotline to denounce cases when the candidate pledge was broken. ACFIM is exploring the possibility of scaling up these interventions during the 2021 Ugandan elections.

Vicente, Pedro C., “Is Vote Buying Effective? Evidence from a Field Experiment in West Africa,” Economic Journal, 2014, 124, F356–F387.

Hicken, Allen, “Clientelism,” Annual Review of Political Science, 2011, 14, 289–310.

Vasudevan, Srinivasan, “Diminishing the Effectiveness of Vote Buying: Experimental Evidence from a Persuasive Radio Campaign in India,” Working paper, 2019.

European Union Election Observation Mission, “Uganda, Presidential, Parliamentary and Local Council Elections,” Technical Report 2016.