Reaching the most vulnerable: Can digitization improve social assistance targeting?

Globally, developing and transition economies spend an average of 1.5 percent of GDP on social assistance. While social assistance has helped reduce poverty, there has been a clear failure in targeting the poorest populations.

Social assistance schemes are non-contributory interventions (i.e. the government or other providers pay the full amount of the assistance) designed to help individuals and households cope with chronic poverty, destitution, and vulnerability. Examples include unconditional and conditional cash transfers, non-contributory social pensions, food and in-kind transfers, school feeding programs, public works, and school fee waivers. Across developing countries, estimates from available household survey data show that on average 7 percent of people escape absolute extreme poverty because of receiving social assistance transfers.

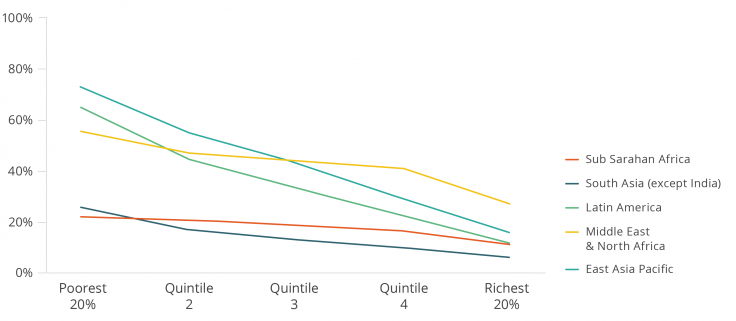

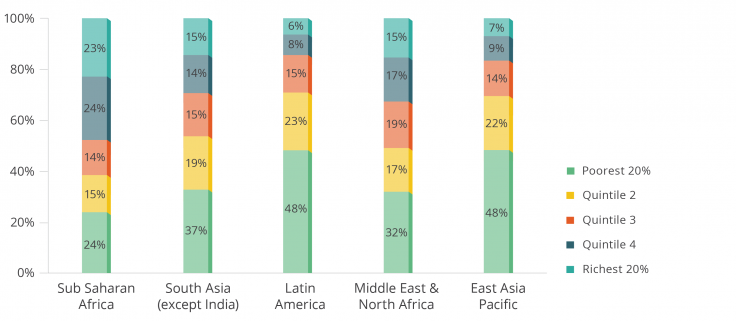

But the most vulnerable are often left behind. According to the World Bank’s ASPIRE database, only 22 percent of the poorest households in sub-Saharan Africa receive any form of social assistance, and only 24 percent of all expenditure on social assistance reaches the poorest quintile on the continent (see Figures 1 and 2). This implies that 78 percent of the poorest people in sub-Saharan Africa receive no form of social assistance from the government. Further, the poorest and richest quintiles receive similar proportions of social assistance transfers making social assistance programs in sub-Saharan Africa the least progressive compared to other regions (Figures 1 and 2).

Source: Parekh & Bandiera, 2020

Source: Parekh & Bandiera, 2020

Accurate targeting is fundamental to successfully implementing social assistance programs. The benefits of social assistance programs are often aimed to reach the poorest people of the country--as typically measured through a means-test or an income-test--but in reality programs that effectively find these beneficiaries can be extremely hard to design and implement. When people are involved in informal or agricultural jobs, they often lack documentation of their wealth making it difficult to accurately measure or verify the income of potential recipients. This challenge is intensified by the absence of advanced social security or tax records. This lack of information can cause some undeserving beneficiaries to enter the program (what we refer to as “inclusion error”) or leave other vulnerable households outside the safety net (known as "exclusion error”). The inadvertent denial of benefits to legitimate participants can lead to potentially dire consequences for these individuals and can also undermine public support for such programs, as well as other state-led income redistribution systems. To what extent and how can biometric IDs and digital financial services (DFS) address both inclusion and exclusion errors?

Improved data & identification

With limited access to banks and formal financial institutions, administrative data (i.e. routine information collected, used, and stored by governments and other organizations primarily for operational, rather than research purposes) on the wealth and income of households remains lacking for poor populations. The introduction of digital identification (ID) systems and DFS provides an alternate and, possibly more precise, solution to this identification barrier.

Digital ID systems can potentially alleviate this lack of accurate income data by facilitating improved record-keeping and generating administrative data on individuals in the country. Digital financial services enables documentation of a person’s financial transactions that can be used to create indices for eligibility. Further, digital government-to-person (G2P) payments could also provide a trove of data that would be linked through identifying factors to create a more robust dataset on beneficiaries. This would allow programs to leverage data collected by other programs. For example, in Togo a digital cash grant targeted to households in the informal sector (Novissi) used the voter ID database—from February 2020 presidential elections—which contained precise location and occupation information, to identify beneficiaries. Of course, centralized detailed datasets could also lead to state surveillance and misuse of data if adequate security measures are not in place.

To support the claim that digital IDs improve targeting, a difference-in-differences study in India found that the introduction of a new technology that allowed for the direct deposit of transfers into a beneficiary’s account in a government transfer program reduced leakages to ghost-beneficiaries (i.e. beneficiaries who did not really exist).

Improved monitoring systems

Further, digitization of payments can lead to more effective process monitoring, which enables implementers to make real-time decisions based on incoming data. This is particularly crucial during unexpected shocks, such as the on-going COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, governments are using innovative digital solutions such as satellite imagery and alternative data sources to reach those most affected by the pandemic. The existence of a mature digital payment and ID system could have greatly helped governments respond to the crisis as seen in the above example from Togo. In a context where there is a reliable identification system in place, digital data collection can make policy decision making easier and more responsive to the needs of the people on the ground.

However, the risk of technology failures leading to exclusion of eligible beneficiaries remains if access to biometric IDs is not universal or systems are not well implemented or managed. This could especially be a problem if more vulnerable populations are left out of the ID system. Further, issues around privacy and data misuse remains a major concern when data is collected and held centrally.

What about stateless groups?

Some populations, including refugees, migrants, and other ‘stateless’ groups, may be particularly challenging to reach or may inherently be excluded from specific ID systems on the basis of nationality/citizenship. In such cases, complementary ID systems may be necessary to reach these populations, in order to facilitate access to social services and increase economic integration.

For example, in Kenya, UNHCR has established a biometric database of refugees and asylum seekers that runs parallel to their national registration system. Elsewhere, efforts are in place to introduce regional ID systems that extend beyond national identity. In West Africa, for example, the West Africa Unique Identification for Regional Integration and Inclusion (WURI) program is being piloted in Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea to provide identification to citizens and non-citizens alike, with the goal of reaching vulnerable populations and facilitating access to services at both the country and regional level.

A word of caution

The integration of ID systems with payments is not, however, a fool-proof solution to targeting problems. Collusion to siphon a portion of the transfers could occur due to imbalanced power dynamics. For example, local bureaucrats may establish sharing agreements where a cash transfer is approved in return for a proportion of the transfer.

Collusion could also occur at the central level through state capture or conscious efforts by administrators or the state to exclude beneficiaries from certain groups, particularly if the ID system is linked to voting rights. Empirical evidence of detecting such collusions is limited and there is tremendous scope to explore and document its existence, as well as possible solutions.

Moreover, if beneficiaries are unable to navigate digital G2P payment systems, they may not be able to access their grants even when eligible, as seen in Jharkhand, India. Here, the use of Aadhaar—a digital biometric identification card—as a digital tool to authenticate beneficiaries, reduced the benefits for those who had not registered for an ID. Given that more vulnerable populations are often also those who have less access to knowledge on technology, this could mean the most vulnerable are particularly susceptible to exclusion when shifting to a digital payment mechanism.

What’s next?

The Digital Identification and Finance Initiative (DigiFI) is currently funding projects on various aspects of targeting using digital systems.

- In Malawi, researchers are exploring whether digital IDs can reduce poverty;

- In Kenya, a study is evaluating the inclusion and exclusion effects of linking digital IDs to social protection programs; and

- In Ghana and Kenya, researchers are studying how digital social transfers can help citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic.

You can read more about our research agenda and existing projects. Yet there is an urgent need for more evidence in sub-Saharan Africa on whether digital systems help achieve accurate targeting and efficiency in public programs and whether such systems ensure more equality for hard to reach and/or marginalized citizens. If you are interested in pursuing research on these topics, please reach out to our team at [email protected].

Author’s note: This is the fourth blog in the DigiFI series on the various aspects of their research and policy priorities. The next blogs will explore to what extent digitization can help tackle corruption and other leakages, better incentivize public administrators, and improve take-up.