Leveraging the digital revolution: Can governments utilize big data to help decision-making?

Globally, there have been 62,844,837 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 1,465,144 deaths, reported to the World Health Organization as of 7:08pm CET, 1 December 2020. These data are updated frequently, often displayed on dashboards in easy to interpret formats, automatically disaggregated by region and country. The information provided is crucial to policymakers to understand and respond to the landscape of the pandemic.

The WHO COVID-19 dashboard is just one example of how institutions can leverage data and display them in ways to facilitate decision making.

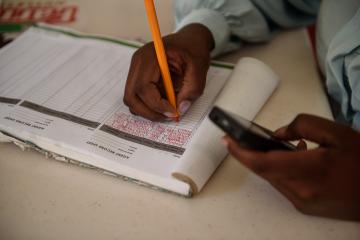

We know the importance of using evidence when making decisions, particularly policy decisions. However, this can be challenging when the information one needs is not credible, easily accessible, or interpretable. This difficulty can be overcome with the use of a monitoring system: a tool that leverages existing data and presents them clearly in ways that facilitate decision making. As governments and organizations move towards more digitized systems, this allows for new data to be regularly collected and easily transmitted. For example, linking social assistance schemes to a digital identification (ID) would allow for regular data on beneficiary take-up and profile of beneficiaries who have and have not accessed their social grant. Hence, the possibility for digital monitoring systems becomes even more attainable.

What are high-frequency process monitoring systems?

High-frequency process monitoring systems allow organizations to track the progress of programs by relying on rapidly collected data and easily interpretable data visualization/analytics. Although these systems may vary in form, a well functioning system usually has the following key attributes incorporated into the design. These elements include:

- Credible underlying data: Monitoring systems are able to easily access data either by leveraging existing data sets or through high-frequency data collection through digital technology. It is of foremost importance that this data is credible.

- Granularity and volume: The data should be varied enough in terms of the characteristics of the population to allow for analysis of the data over different attributes (such as geography, age, gender), and be from a large enough sample in order to conduct basic data analysis.

- Easy-to-interpret presentation: Monitoring systems are set-up to enable a quick assessment of programs in short time frames to be able to make changes according to ground realities. It is key that the data is presented in formats that are easy-to-understand and analyze. For example, monitoring dashboards or regular automated reports.

- System with aligned goals: As the set-up of a monitoring system brings together researchers and policymakers, it is essential that there is a clear understanding of the goal of the monitoring systems. Researchers would be required to understand the policy context and co-generate actionable insights with such systems. Policymakers would also be required to understand the process of researchers, the need for access to data, and researchers long-term goal of using this data to explore policy-relevant research questions.

Benefits to government officials and policymakers: Implementation assistance and faster monitoring timelines

Improving implementation: Technological innovations for monitoring could improve the administrative implementation of social protection programs. For example, in partnership with the Ministry of Rural Development in Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand in India, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation of a new internet- and mobile-based management and monitoring platform, PayDash, to improve the functioning of the world’s largest rural employment guarantee scheme. The platform tracked when each step in the payment process occurred and generated real-time information on delayed payments. This in turn was linked to information on employees responsible for each administrative step. PayDash presented this information in a more accessible and actionable format to government officials who were trained to use it. Platform access significantly reduced wage payment delays in areas with worse baseline performance.

We see huge potential in setting up high-frequency monitoring systems for tracking digital ID systems as they roll out and are linked to other services. The benefit of digital data collection means that Registration Authorities could monitor how many people have been registered, along with the take up of the ID card, which often happens as a second step to registration. In addition, officials would quickly be able to tell how many digital IDs have been linked to different government programs, plus the profile of those who access the programs every month. These data could be essential for predicting the take-up of welfare programs in the future months and hence, the expected budget requirements for the future as well as improved targeting of the programs.

There is evidence to support the positive effect of using high-frequency monitoring systems on program implementation and decision-making. Phone-based high-frequency process monitoring systems have been found to improve last-mile service delivery for cash transfers to farmers in India. The implementation of a high-frequency process monitoring system led to a 7.2 percent decline in the number of beneficiaries not receiving their transfers. Even if not fully digitized, the phone survey data used as a complement to the existing administrative data proved a cost-effective way to collect information from hard-to-reach locations at frequent intervals.

Faster turnaround: Academic research projects often have long timelines. However, governments often need data and results quickly to inform decisions. Data from high-frequency process monitoring systems can be especially useful for government officials who would like to understand how the program is progressing, make quick changes to program elements, or refine their implementation plans, particularly during the piloting stages of a program.

In addition, where political cycles are short, the fast turnaround of results from digital monitoring systems allows for process monitoring outcomes that align more to these political timelines. The rapid turnaround of information could be useful to policymakers and assist them in pivoting on decisions based on the roll-out of programs.

Benefits to academics: Building relationships, understanding context, and reducing data collection costs

Expanding data available and reducing costs: Investing jointly with policymakers on setting up high-quality, high-frequency monitoring systems can have huge benefits for researchers by expanding high-frequency datasets available for research. Typical evaluations have one baseline, one midline, and one endline. High-frequency datasets collect data more often than these typical studies and therefore allow the researchers to get a more detailed understanding of their beneficiaries. Monitoring systems often use existing administrative data, which can be leveraged as part of the full evaluation, thereby reducing data collection costs.

More objective data collected: Monitored data, if collected through administrative systems often measure certain features more objectively (for instance, rather than relying on self-reported data), is collected at a much higher frequency than researcher-collected data and the large scope of the data has the potential to be more representative of a broader population. Finally, information about program implementation is often critical to understanding the nuance of the impact measured by an evaluation, and monitoring systems provide an option to measure this objectively and accurately, as opposed to relying on self-reported or incomplete information from program implementers.

Useful for relationship building: Researchers who set up high-frequency monitoring systems can develop stronger relationships with government officials and the associated departments. The monitoring work allows them to build a deeper understanding of existing government systems and availability of data prior to implementing a full-scale evaluation. In addition, setting up these data access systems more broadly is a public good. During this time, researchers can pilot certain systems in preparation for a larger study and also establish, with a higher degree of certainty, if the implementation of the intervention is possible.

DigiFI’s interest in high-frequency process monitoring systems

The Digital Identification and Finance Initiative in Africa (DigiFI) is encouraging researchers to collaborate with governments to develop high-frequency process monitoring systems within digital identity and/or digital social payment systems. As a complement to longer-term, evaluative research, these systems are an important way to support government decision making which often have short time frames. Possible outcomes could include tracking delivery, reach, and/or take-up of an intervention. This data could be crucial to understanding how to roll-out digital ID and payment systems, and leverage the data being collected as governments go digital. This data could also prove very useful to policymakers to monitor a new program in real-time and make changes accordingly. Further, the data collected from monitoring systems can be used as a stepping stone in building lasting relationships and evidence co-generation between researchers and policymakers.

DigiFI is excited to support more high-frequency process monitoring systems. Policymakers interested in setting up such systems and researchers interested in working on these systems, with the intention of building to a full randomized evaluation, should reach out to the DigiFI team at [email protected].

Extra resource: J-PAL recently launched Handbook on Using Administrative Data for Research and Evidence-Based Policy

The handbook serves as a go-to reference for researchers seeking to use administrative data and for data providers looking to make their data accessible for research. The handbook is edited by Shawn Cole (Harvard Business School), Iqbal Dhaliwal (J-PAL), Anja Sautmann (World Bank), and Lars Vilhuber (Cornell University). Read the handbook.

Authors Note: This is the penultimate blog in the DigiFI series on the various aspects of their research and policy priorities. The next blog will focus on gender and digitization.

Related Content

Overcoming under-subscription of welfare programs: Digital solutions to low take-up

Incentivizing public sector employees: The role of digital technology in enhancing the carrot and the stick